For the 132nd episode of the Journalism History podcast, journalism historian Gerry Lanosga describes the investigative reporting techniques used by abolitionists in the early 1800s to counter lies and disinformation spread by slaveholders and their allies.

For the 132nd episode of the Journalism History podcast, journalism historian Gerry Lanosga describes the investigative reporting techniques used by abolitionists in the early 1800s to counter lies and disinformation spread by slaveholders and their allies.

Gerry Lanosga is associate professor at the Indiana University Bloomington Media School. His research interests include the development of journalism as a profession, prize culture in journalism, and journalism’s intersections with public policy.

Transcript

Gerry Lanosga: It’s this whole idea of shining a light on something that is going to really educate somebody who’s ignorant about a wrongdoing that’s happening.

Ken Ward: Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to reexamine the stories you thought you knew, and the ones you were never told.

Teri Finneman: I’m Teri Finneman, and I research media coverage of women in politics.

Nick Hirshon: And I’m Nick Hirshon, and I research the history of New York sports.

Ken Ward: [00:00:30] And I’m Ken Ward, and I research the journalism history of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

And together, we’re professional media historians guiding you through our owns drafts of history. Transcripts of the show are available online at journalism-history.org/podcast. This episode is sponsored by Taylor & Francis, the publisher of our academic journal, Journalism History.

The 1900s offer great examples of investigative reporting that have shaken awake audiences, inspired journalists, and strengthened the democratic [00:01:00] process in the United States and other places around the globe, but as today’s guest explains there’s no reason to limit our attention to the 20th century.

In this episode, Dr. Gerry Lanosga, an associate professor in Indiana University’s Media School, walks us through the development of investigative reporting in the early 1800s by abolitionists who found themselves searching for new ways to counter lies and disinformation spread by slaveholders and their allies. As Lanosga explains, the resulting practices used [00:01:30] by abolitionists were very much in-line with those used by investigative reporters today. Gerry, welcome to the show. So, you start this article about investigative reporting at Watergate, why do you start there?

Gerry Lanosga: Well, this article appeared in a special issue devoted to the history of investigative reporting tied to the Watergate anniversary, and Watergate is that big cataclysmic event [00:02:00] in American politics that for a lot of people serves as a stand in kind of idea for the power of investigative reporting and so when I saw the call, I thought, “I’ve gotta do something for this,” because I’m a former investigative reporter, I study the history of the practice of investigative reporting and really my mind went immediately to the abolitionists, but I wanted to situate it in, you know, for purposes of the special issue… and also as a kind [00:02:30] of a justification for the article that, you know, Watergate serves as a touchstone for a lot of people when they think about investigative reporting, but it really as a practice, it goes back a lot further.

Ken Ward: Sure, so as- as you mention, your focus is on the abolitionists, so why don’t you take us way back and explain to us, how do the abolitionists get interested in investigation more broadly, right, and- and when are we talking about here? And- and additionally, are these people that we would recognize [00:03:00] as journalists, or that we would call journalists?

Gerry Lanosga: That’s a great question. Um, I’ll get to the part about whether they thought of themselves as journalists, and whether we would think of them as journalists in a second, but just to give you broad strokes of- of the overview, abolition as a movement really goes back to the late 1600s and it really started with the Quakers and of course, you know [00:03:30] thinking of that, it was largely a religious movement and a lot of the critique of slaveholders at the time was based in religion. Many of the critiques, many of the pamphlets that were written were biblical exegesis, with the idea of, you know, trying to persuade people that they were sinning by holding people in slavery… um, this- this strategy of moral suasion, and that really gets started in the 1600s.

[00:04:00] And there’s a, you know, a steady stream of abolitionist writings throughout the 1700s. My focus in the article is really on the 1830s, which I kind of think of as a second wave of abolitionism that takes a more radical tone to it, and writers at that point are really thinking about exposing the realities of slavery as a strategy to call into- call to attention the sinfulness, [00:04:30] uh, of the practice, and so I’m really focused on some of writers that are pretty well-known such as William Lloyd Garrison Lydia Maria Child the Grimké sisters, Theodore Dwight Weld, in the 1830s who may not have thought of themselves explicitly as journalists first, although they certainly were.

Many of them wrote for newspapers, for instance. William Lloyd Garrison, of course, started his own newspaper, [00:05:00] so he was a journalist… that word was certainly in use at the time. Um, you know, they were journalists who were, who were much different from the ones that we think of today. They were prone to fiery rhetoric, emotional appeals. They certainly had a religious drive, and a religious motivation so they may have thought of themselves more as evangelistic or even activist, in a way but certainly what they did, you know, if you stripped it [00:05:30] of all the other things, it certainly meets all the sort of qualifications or the definitions we have of investigative reporting today, so I think, we recognize what they do- did – as journalism, and that’s certainly what- what my argument in the article is.

Ken Ward: So especially in the earlier parts that we’re talking about here, the earliest era of this type of reporting in the 1800s, when we say, investigation, what- what types of investigations are they doing, what- what information are they looking for, and how are they presenting it to the audience [00:06:00] in the beginning?

Gerry Lanosga: Once this emphasis on evidence really hits its stride in the 1830s, they’re- they’re looking at all the sorts of things that an investigative reporter today might look at. They look at official records from judicial proceedings, for instance they get testimony from witnesses… interviews, in other words. Um, they go look at newspapers, [00:06:30] sermons, you know, pamphlets, all sorts of things that could serve as tangible sort of credible authoritative evidence of something that was going on with slavery, as opposed to earlier accounts which certainly were, you know, were not certainly – were interested in exposing realities of slavery, but they were much more sort of emotionally based.

They would make sort of statements about [00:07:00] the cruelties of slavery without really explicitly engaging with the idea of, “Here’s how we know what we’re telling you about slavery,” and so basically they were doing all the things that journalists do today, that investigative journalists today, going and talking to people, looking at the documentary record and not only looking at those things and incorporating it into their work, but – into their work, but really explicitly talking about that- that the importance of the evidence, [00:07:30] um, both in their publications and in their correspondence with each other about how to, how to do this work.

Ken Ward: And- and can you give us a sense, what does the abolitionists press look like in the – your article’s really focused there on the 1830s. Are we talking about lots of newspapers, pamphlets, what- what- what does it look like, what would we be reading this material in?

Gerry Lanosga: It’s definitely both. There’re a lot of newspapers, such as The Liberator, that comes along in 1831 and a lot of pamphlets, such as Genius of Universal [00:08:00] Emancipation, I might think of as a, as a little bit of a hybrid there, but that one starts in 1821 with Benjamin Lundy and the American Anti-Slavery Society in the mid-1830s. It had been around for a while, and had been publishing pamphlets but it really put on a hard press in the middle of the 1830s to blanket the country in pamphlets, so these would be, you know, some one-off publications, you know, folk that- [00:08:30] that would be short. They were not necessarily periodicals… sometimes they would be republished, but they blanketed the country in more than a million pamphlets, for instance.

So, we’re talking about a lot of different things, not just sort of traditional newspapers, as such.

Ken Ward: Sure, so in your paper, you argue that Garrison’s – and I think that’s the book or pamphlet – and the line there seems so- so difficult, right, but this- this publication called Thoughts on African Colonization,-

Gerry Lanosga: Mm, mm.

Ken Ward: … you argue this was a turning point [00:09:00] in investigative reporting. So can you tell us a little bit more about Garrison and The Liberator, his newspaper, and- and then explain to us, why was Thoughts on African Colonization, this book or pamphlet so important in this development of investigative reporting?

Gerry Lanosga: Sure, so Garrison, like many abolitionists started out in the 1820s with the idea that we can do this gradually, and we might do it – we might have abolished slavery, for instance, by, [00:09:30] taking free former slaves and formerly enslaved people and sending them away, sending them out of the country, colonizing them, in other words, in another place, and that was a fairly… probably the predominant line of thinking in the 1820s among white abolitionists, I should say. Um, but there was also at this, at the time in the 1820s, this sort of developing [00:10:00] Black protest movement that involved pamphleteers and conventions in societies that African Americans were founding at the time, that were making the argument against colonization.

They didn’t want to leave the country, and they didn’t want gradual emancipation, which they thought really was only allowing slavery to continue, you know, in perpetuity and Garrison and others… but Garrison, [00:10:30] uh, you know, kind of in a leading role, became persuaded by these arguments and so in 1831, when he founded his newspaper The Liberator, he really had made a full transformation from a gradualist to what was called immediatist calling for immediate abolition and he really – to start off his crusade with The Liberator, he turned his attention to the [00:11:00] American Colonization Society, the ACS, which was the organization that was advocating for this gradualist position.

Um, and he put together a book called Thoughts on African Colonization, published in 1832. It was more than 200 pages. He talked repeatedly about evidence, such a mass of evidence that he pulled from publications of the ACS, sermons, conversations with people, and a lot of articles [00:11:30] from the African Repository, which was the house newspaper of the American Colonization Society and really spent a lot of time juxtaposing the claims with reality… that these were people who claimed to be against slavery, but really if you peel back the, you know, the veneer there, under the surface it’s a lot of support for slavery.

Uh, they- they weren’t going to oppose the idea of holding people as property, for instance. And so he juxtaposed [00:12:00] these stated views with what was really going on in the sermons, and so forth and the lack of credibility of the colonizationists with extensive exhaustive footnotes. And then he kind of countered that with the idea that the evidence he was presenting was credible and authoritative basically hanging the colonizations, or the colonizationists on their [00:12:30] own words.

Ken Ward: And so this was a new idea, right, or at least relatively new. Can you tell us more about that… do you get a sense, were there, were there other places where this type of verification was occurring in the press, or is this a fairly unique episode that came out of this abolitionist movement? Do you, did you get a sense of that during your research?

Gerry Lanosga: My argument is that this is innovative. Not to say that there weren’t some one-off examples [00:13:00] of people doing investigative reporting… what we would call investigative reporting, because by the way, that doesn’t… that phrase, investigative reporting, or investigative journalism, doesn’t even come along until the mid-20th century the best-

Ken Ward: Mm.

Gerry Lanosga: … I can tell. Um, but people were doing exposure journalism, whatever they called it, 100s of years ago, and certainly in the colonies before, you know, the United States was founded, there were examples of things [00:13:30] where reporters had, you know, journalists or printers had exposed hidden wrongdoing by using documents but not in a systematic way, and… so I really do think what happens with the abolition writers, and explicitly so, is that they’re talking about a method for not only exposing wrongdoing, but for documenting, you know, the claims about that wrongdoing… and you don’t see it in a real systematic [00:14:00] sort of broad way until it comes into its own as part of this activist movement of abolitionists.

Ken Ward: So, is it sustained, right, so we see this idea pop-up here. It’s sort of we can point to Thoughts on African Colonization as a model of that… does it continue, does it spread throughout the abolitionists’ movement, do other people take up this idea of, okay, it’s not just about presenting information, [00:14:30] but presenting verified compelling information to actually persuade people that our cause is- is not only just, but correct?

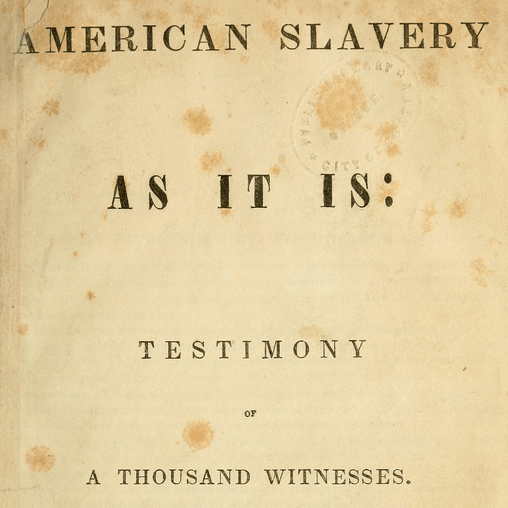

Gerry Lanosga: Yeah, so Thoughts on African Colonization‘s published in 1832, and I do think it spreads, at least in the immediate decade, and one of the key figures I focus on is Theodore Dwight Weld, who was an anti-slavery agent. He was commissioned by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1834 as the agent for Ohio, and his [00:15:00] commission explicitly instructed him that his goal was to show the public the true character of slavery, to expose hidden truth with FACTS and FACTS is in all capital letters in the commission. Um, and it also explicitly referenced Garrison’s Thoughts on African Colonization as a model for doing that, for how to build an evidence-based argument, and so, Weld and other writers [00:15:30] in the 1830s do use that as a model, and it is explicitly used as a model for what, I think, is kind of the masterwork of the era, which is American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, which Weld published with his wife and his sister-in-law in 1839.

And it is really an amazing document to read. It’s what got me interested in this whole idea in the first [00:16:00] place, because there was an actually circulating copy of the original printing in our university library at Indiana University, which I was just amazed by-

Ken Ward: (laughs).

Gerry Lanosga: … and reading it is just astonishing. It’s a – it’s a compendium of facts and the evidence footnotes in the annotation and it’s just a fascinating thing to read.

Ken Ward: Well, so let’s – let’s explore that just a little bit more, because as I was reading your article, Weld’s approach seems fairly sophisticated, right, and it acknowledges, or it seems to me [00:16:30] to acknowledge that eyewitness testimony isn’t enough, which when you read some of the examples that you provided in the article alone, right, just a few, you know, the testimony is extremely compelling, but they’re recognizing in this era that eyewitness testimony isn’t enough. It needs verification. There needs to be more work behind it to actually be persuasive. How did they come to that view, what made them, you know, where did that spark come from that said, okay, the stories aren’t enough. We need [00:17:00] proof behind them?

Gerry Lanosga: Yeah, that’s interesting. I think there’s a, just a sense that develops over, you know, more than a decade of advocating for abolition that, you know, the Southern plantation class is not just sitting there reading and – and listening to things. They’re talking back, and in their arguments, they make arguments [00:17:30] about well, the myth, er, you know, you’ve – you may have heard the phrase, The myth of the happy slave. This is the idea that people who are enslaved on plantations are really happy, they’re well-treated, they’re well-fed and taken care of, and really they’re in the position in society that is the best and highest use for them.

And so there’s this rhetoric that is being put forth by Southerners, and in [00:18:00] many cases, you know, being if not avidly believed, being sort of allowed for in the North, among people who may not have gone to the South, they don’t really have a sense of what things are really like, and even those who have gone there, as Angelina Grimké pointed out in one of her speeches, she said, you know, people sometimes go to the South, and they enjoy Southern hospitality, but they never really peer into the dark corners, and so [00:18:30] what we need is not just arguments and logic, but we need testimony and we need facts, and eyewitness testimony was part of that, but it was much more powerful when it was verifiable.

Um, and so in some ways the evidence from fugitive slave ads, for instance, that were run, you know, in Southern papers all the time describing the terrible injuries [00:19:00] that some of these fugitives bore from their time working on plantations and so forth, those sorts of evidence could be much more powerful than the eyewitness testimony alone. And so when they were putting together this book, American Slavery as It Is, they sent out – Theodore Dwight Weld sent out a form letter around the country to as many people as he could think of, abolitionists and people that lived in the South seeking evidence, testimony, [00:19:30] and some of the, (laughs), the rhetoric is just incredible. I think, you know, as a person who teaches investigative reporters today, I think about a quote that he said uh, that could be a good kind of rallying cry for investigative reporters today, “Give facts a voice, and cries of blood shall ring till deaf ears tingle.”

It’s this whole shining a light on something that is going to really educate somebody who’s ignorant about [00:20:00] a wrongdoing that’s happening.

Ken Ward: Sure, well, the abolitionists’ movement splinters… if I understand right, soon after publication of that- that book by Weld, or that pamphlet American Slavery as It Is, so if the abolitionists’ movement kind of splinters, how was this like thought technology of verification perpetuated? How does it continue and sort of diffuse throughout journalism?

Gerry Lanosga: Well, one, I think, it’s there in the background. It’s there in the history of journalistic practice, [00:20:30] and I think mainstream journalists are paying attention, and so perhaps a decade or so after American Slavery as It Is gets published, for instance, you start to see some exposes in mainstream newspapers of the horrors of slavery, the evils of slavery. Um, I don’t have a record of correspondence that or, you know, or diaries [00:21:00] of these journalists from the mid-1800s that profess to kind of owing a debt of gratitude to these abolitionists for pioneering a method, but my hunch is that they’re- they’re certainly inspired by and drawing from those practices that were established a decade or so before, and then throughout the 19th century you see examples of the documentary method being used by a number of different [00:21:30] journalists. There’s a wave of sort of a crusade reporting that happens in the 1870s.

And then we kind of steam into the turn of the 19th into the 20th century with the muckraking movement, and all of those are not really that far removed from the abolitionist efforts to sort of pioneer this method of connecting the exposure to the idea of evidence.

Ken Ward: So, with all [00:22:00] this in mind then, how ultimately do you think our understanding of investigative reporting today should change based on what you present in this article from the abolitionist movement?

Gerry Lanosga: I just want people to have another touchstone for thinking about investigative reporting as a, you know, a critical piece of journalism, which is itself kind of a critical piece of democratic governance, I think. I want there to [00:22:30] be a different touchstone, in addition to Watergate, which is the touchstone for a whole generation of people, maybe the – especially the baby boomer generation – and there are other more recent touchstones, such as the Spotlight movie about the Boston Globe investigation into abuses by the Catholic priests in the Boston Archdiocese… those are touchstones that make people think about what the potential is for investigative reporting, for journalism really to have [00:23:00] some sort of power in society, and I think to the extent that we kind of limit our view of those things as being, really, you know 20 years ago, or 50 years ago, that just limits our sense of the history in general.

And, I think, it’s important to kind of get that right to know that Woodward and Bernstein didn’t necessarily innovate things that they were doing in the ’70s, that these [00:23:30] things have been going on for a while.

Ken Ward: Sure, well listeners of the show know we have one last question that we like to ask all of our guests. I’m interested to hear your response, Gerry. “Why, in your opinion, does journalism history matter?”

Gerry Lanosga: Well, really related to the answer I just gave you about investigative reporting, journalism has been called the dialogue of democracy, I think, David Broder said that, and my own adviser, [00:24:00] Dave Nord, called journalism the literature of politics, and so, if you think about democracy and, as an important thing in America, and journalism as the literature of that thing, then it becomes important to really understand that history, and I would say, in general, you know, history matters, (laughs) to know where we’ve been, how we got here for instance, and given that we live in a system of democratic governance, [00:24:30] and journalism is the means by which people kind of understand that system, I think it’s really important to understand history of it as well.

And it can really inform how we approach the practice of journalism, for instance, today, and the way we think about how journalism ought to be a part of that political ecosystem, and so it can really serve as a way that we think about, for instance, what do we do to make journalism survive [00:25:00] into the future?

Ken Ward: Absolutely, well Gerry, I really appreciate you being on the show. Thank you so much.

Gerry Lanosga: Thank you, Ken, really appreciate the conversation.

Ken Ward: Well, that’s it for this episode. Thanks for tuning in, and be sure to subscribe to our podcast. You can also follow us online on Twitter @JHistoryJournal, that’s all one word. Until next time, I’m your host Ken Ward signing off with the words of Edward R. Murrow, “good night, and good luck.”