For the 131st episode of the Journalism History podcast, Biographer Beverley Buller discusses William Allen White, known as the Sage of Emporia, and how this Kansas newspaper owner became a national phenomenon whose home remains a tourist attraction today.

For the 131st episode of the Journalism History podcast, Biographer Beverley Buller discusses William Allen White, known as the Sage of Emporia, and how this Kansas newspaper owner became a national phenomenon whose home remains a tourist attraction today.

Beverley Olson Buller is a teacher and librarian who recently retired after 40 years. She is the author of four books including From Emporia: The Story of William Allen White and A Prairie Peter Pan: The Story of Mary White, which were both named Kansas Notable Books and chosen for the Kansas Reading Circle catalog and the William Allen White Award master lists.

Transcript

Beverley Buller: A clean, honest local paper, and that really is what he always aspired to do. He would always call it a country paper, and he would call himself a country editor.

Teri Finneman: Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to re-examine the stories you thought you knew and the ones you were never told.

I’m Teri Finneman, and I research media coverage of women in politics.

Nick Hirshon: And I’m [00:00:30] Nick Hirshon, and I research the history of New York sports.

Ken Ward: And I’m Ken Ward, and I research the journalism history of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Teri Finneman: And together we are professional media historians guiding you through our own drafts of history. Transcripts of the show are available at journalism-history.org/podcast. This episode is sponsored by Taylor & Francis, the publisher of our academic journal, Journalism History.

What’s the Matter with Kansas? [00:01:00] It’s one of the most famous editorials in journalism history. Yet unless you live in Kansas, you may not be familiar with the name William Allen White, even though presidents and people around the nation once clamored to hear his opinion. Even I wasn’t aware of him until I began working at the journalism school named after him. Now I make sure students know what a remarkable community journalist he truly was.

In today’s episode, we delve into White’s story and Midwestern journalism [00:01:30] history with biographer Beverley Buller.

Beverley, welcome to the show. Before we talk about White, tell me why you think it’s important to study figures in Midwestern journalism history.

Beverley Buller: Yes. I think, first of all, it is so interesting how many great journalists in the history of journalism have come out of the Midwest. Probably within a frame of reference for the people listening to this, we’re going back a [00:02:00] little bit here, but, you know, Walter Cronkite was from Kansas City. Here in Kansas, we had Jim Lehrer. Bill Kurtis cut his teeth in Topeka, Kansas. So we have all of those great journalists, and they are, I feel, examples for anyone aspiring to become a journalist. And if you go back far enough, of course, you have William Allen White. But I think mainly it’s these people who made a career from journalism and became household [00:02:30] names like William Allen White.

Teri Finneman: How did White get interested in the newspaper business?

Beverley Buller: Well, in his autobiography (laughs) he claims … Of course, he had a satiric way about him and he liked to laugh. And his … in his autobiography he frequently makes light of some subjects that could be considered very serious, and this is one of them. He claimed that it was just all a matter of chance that he ended up in journalism because when he was [00:03:00] about 12, his father said that he needed a job, and he was going to find him a job. And evident – Of course, the father was mayor of El Dorado at the time, so he had a lot of connections in El Dorado, Kansas. And according to Mr. White, the father considered placing his son in a grocery store, but also in a local newspaper, and the newspaper won out.

So he became a printer’s devil, which meant [00:03:30] he picked up type off the ground. He swept, you know, probably every evening, swept the newspaper shop out, emptied the trash, you know, did odd jobs. So that was how he started. He got to observe a small town, this was El Dorado, Kansas, newspaper, and how it ran.

He also was able to see the amount of influence that a journalist, that a newspaper owner-editor back then had because [00:04:00] this gentleman would be gone from his job going to Topeka to cover things, but I think also to do a little lobbying. Now, that job didn’t last very long because Mr. White found out that his father was writing the check, so he did not work past the one paycheck. And we do have a copy of that check.

So, and that … But that didn’t sour him because he continued to have an interest in newspapers. And when he went to college, first at Emporia, he worked at the local [00:04:30] paper there. When he transferred to the University of Kansas, he worked not only for the daily paper on campus, but also for the Lawrence paper. And, uh, that went from there. Because back then, there was no journalism school.

So when he was offered the management of the El Dorado Republican over the Christmas holidays of his senior year at KU, he took it. And that was the best training he could’ve had because, [00:05:00] once again, the editor of the, and the owner of that paper was in Topeka. And so Mr. White ran that paper and that, that was his journalism school.

And so, he had printer’s ink in his blood and knew that he wanted to own his own paper. Now, when he met Sallie White, who – that was his wife, of course. She lived in Kansas City, and he had worked for a couple of Kansas City papers, ending up at The Star. He went up there, I think, about [00:05:30] 1891. And he and Sallie agreed once they were married that they wanted to own their own paper. So he began seriously looking around the state for a paper in a … They wanted a college town because they wanted a town … They really wanted a paper like in Lawrence, but they wanted a college town that would have plenty of culture and interesting issues that could be discussed in the paper and a railroad that he could get on to go places outside of Kansas. [00:06:00] And, of course, they found The Emporia Gazette in 1895. And that was it.

But it’s interesting that I think he discovered that he was interested in newspapers because of this, this job that his father basically forced him to have. And that just set his path.

Teri Finneman: What do you think his mission was for The Emporia Gazette? In other words, what did he think was the role of a small town newspaper?

Beverley Buller: You know, he wrote a very famous editorial in June of 1895, where he [00:06:30] said that, you know, “I hope to always sign my name from Emporia,” which right there tells you he was not planning to always be in Emporia. That was going to be his home base. But he says in that same editorial that he was gonna run something … I think he said something like a clean, honest local paper. And that really is what he always aspired to do. He would always call it a country paper, and he would call himself a country editor. But when he [00:07:00] met Dr. Mayo, he called himself a country doctor. So I think there was a bit of that same thing going on there.

But he really was a town booster. He practiced community journalism before we really even knew that that was a thing. He got wire service as soon as he could so that he could have national news in a timely fashion. But he always focused on local. And, in fact, when they first bought the paper, his wife ran the society [00:07:30] column. And I mean, back in that day, it was a real society column, you know, who had lunch where and who wore what? And that was what … He tried to publish what people wanted to read. Uh, and, of course, in many cases, that was local. He made most of his money for the paper with advertising, and that’s the way it was back then as well. So it was a local paper. Um, he called it honest. He did his very best to be kind, I think, always and to be honest. He [00:08:00] tried to keep the paper out of debt.

But, you know, I don’t think he could have run that paper without all of his other jobs. You know, he wrote for magazines. He wrote books. He received … In later years, he had speaking engagements. And he really plowed a lotta that back into running the newspaper.

And, you know, by 1900, he had built a new building. So yeah, he wanted it to be a country newspaper, but by the time he had really reached [00:08:30] the pinnacle of his success, people were subscribing to the Gazette on both coasts, mainly ’cause they wanted to read his editorials.

Teri Finneman: And we are definitely gonna move into that next. So one of White’s most famous pieces was called “What’s the Matter with Kansas?”, which ran in 1896. What was the piece about, and why did it blow up so much?

Beverley Buller: Well, we don’t have time for the whole story, and it’s been printed many places as to what prompted him to write that editorial. But that editorial was written in haste [00:09:00] after he had one of his many run-ins with a group of Populists. Populists were all over, really, the South and this part of Kansas and, and even the East Coast a little bit. And so, the editorial was poking fun at the Populists. And I mentioned earlier that he was often, you know, satiric. And that is exactly what he did in that, in that particular editorial.

He had no idea that it was going [00:09:30] to go viral. He said later, “I just wrote it for my local readers.” But it got picked up. And even President McKinley and other Republican people who were running for office or in, in McKinley’s case, reelection, used it. It hit a nerve across the nation.

But what’s interesting with that editorial, which was his first famous one … He received no awards for it, other than that got his name out there. But it got his name out there nationally because, like I said, it [00:10:00] did speak to something that people were feeling. But locally, including across the state, there were Populists, and they were not (laughs) happy with him. In fact, his compositor, I believe it was, was herself of Populist leaning. And she almost didn’t print it because he had given it to her to set in type, and then he had gotten on a train to go out to Colorado for the summer. And she joked later, “I almost didn’t print it.”

But it … So people in Kansas … In fact, some [00:10:30] who just heard the title of it were angry. “Well, what is the matter with Kansas? What is Mr. White really saying?” So, you know, in some ways, yes, it made him famous across the United States. But it brought heat on him in his own state that he was always trying to, I think, always trying to make up for. And he made a big deal really throughout his life. You know, “It’s Kansas Day. Let’s celebrate our state.” He wrote plenty (laughs) of those type of editorials later. But, yes, that was his first, and that [00:11:00] was his first famous editorial, and it did indeed blow up.

Teri Finneman: So for college students who may not be familiar, can you just talk a little bit more about what exactly he was criticizing about the Populists?

Beverley Buller: You know, the Populists was considered the people’s party, and they were predominantly made up of groups of farmers. They were very scornful of the wealthy, anybody that had wealth. And Mr. White was, you know, in his own way … Well, his father had been mayor of El Dorado. So he had a certain standard, and he was just so scornful [00:11:30] of them. And he said, “They’re just dragging the state down.” And that’s what’s the matter with Kansas is, is this particular political party.

And he had had dealings with them in El Dorado. In fact, they even took a suit … Because, of course, back then, White always wore a suit. They had taken a suit, stuffed it full of straw, and wrote “silly Willy” and burned it in effigy after they paraded it through the main street of El Dorado. So he had had run-ins with Populists before. And [00:12:00] like I said, I think this editorial just blew up.

Like if you were a Democrat nowadays and you just got sick of hearing the other side, you might do something like this. But nowadays, you’d probably do it on Twitter. And he did it. He dashed off that editorial. But it was, it was written in response to what was going on not just in Emporia, but around our state and other parts of the country. And that’s why I think it hit a nerve. He was very genuine in what he wrote, [00:12:30] and you could feel his, his concern and his disgust –

But the thing about Mr. White, he always said, “Consistency is a paste jewel.” It’s really not worth anything. And he was not consistent because in later years, like by 1912 when he got involved with the Bull Moose Party, he was literally Progressive. So he never was too far ahead of what was going on, but some of the things he made fun [00:13:00] of back in 1896, he later embraced. And you can see that in his later editorials. But that’s … I think that’s a good thing that he’s willing to grow with the times and change. And at- In 1896, that editorial expressed the feeling that many people, even outside of Kansas, had.

Teri Finneman: Yeah. So let’s expand on that. In the following years, how did White use the power of the editorial page to fight for change, and that led him, led to him being [00:13:30] known as the Sage of Emporia?

Beverley Buller: And as I mentioned, people outside of Emporia would subscribe to the Gazette because they (laughs) wanted to know what, you know, “What’s White talking about now?” He, as I mentioned earlier, addressed local issues a lot. So his editorials might be concerned with that group of boys who were chasing a pack of wild dogs on the schoolyard. Or they might comment on, “Have you noticed so-and-so’s flower gardens? There’s something [00:14:00] about a flower bed that just shows people care.” You know, things like that. He would comment … At one point, they needed, he felt, a new YMCA. So he went to bat for that through his editorials.

But also, he would use his editorials because he did not spend 12 months out of the year in Emporia. He went to Colorado. He went to both coasts a lot, mainly the East Coast. So he would write editorials on things that he … A lotta times, he was responding [00:14:30] to things that were in the national news. For example, women’s suffrage. He really went to bat for that and wrote several editorials about the importance of that.

He began being called the Sage of Emporia when he was about 65. And think about that. That would’ve been … 65 was considered quite old when White was 65. (laughs) So all of a sudden, he was the Sage. And, you know, I think in many ways he was. By the time he was 65, [00:15:00] he had buried a daughter. He had buried both of his parents. He had been through a World War, had gone over to France and been able to observe it. Um, he had … I think he was in many ways a voice of reason through his editorials and through the subject matter that he chose to put in his newspaper. People around the world trusted him. He was like not just from … He was not just from Kansas. He was, [00:15:30] he was, uh, just a voice of reason, and people wanted to hear what he had to say on different subjects. And they did consider him at age 65 a sage.

Teri Finneman: For a journalist out in the middle of Kansas, White had tremendous influence with the White House. Talk about his relationship with presidents and why they sought him out.

Beverley Buller: Yes, I mentioned that his relationship with McKinley grew out of What’s the Matter with Kansas? And that colored his [00:16:00] response for the rest of his life, I think. He wanted presidents to like him. He wanted presidents to trust him. And, in turn, most of them did. They wanted to know White, or at least in McKinley’s case, to correspond. McKinley mainly used Mark Hanna to correspond with White. White met him once on a … I believe the train came through Emporia, and White got on the car and went and met him. I mean, he didn’t visit [00:16:30] the White House, that I remember.

Um, and so … But that made him realize, you know, “If I know the President, and the President knows, me, that’s gonna help both of us.” Teddy Roosevelt, of course, ended up being one of his best friends. He met Teddy when he was in charge of the Navy. And then, of course, he was able to visit him at his home and also at the White House once he became president.

He wrote books about Wilson. He wrote two books [00:17:00] about Coolidge. And I noticed, he would always be complimentary of presidents, for example, Harding. Harding ended up being not one of our best (laughs) presidents. But when he was first in office, White was supportive of him. And about six months in, would he, you know, tell people, “You know, I’m pleased. He’s doing okay. I wasn’t sure, but he’s doing okay.” Well then, of course, he had to go back on that.

Um, let’s see. [00:17:30] Oh, and FDR. FDR, of course, was a Democrat. And so, he and White had a running joke that White could be his friend three years out of four. In other words, in an election year they would have to not be on the same page. But in many ways, they were. And FDR called on the Sage of Emporia when World War II had broken out. In those years or those days before Pearl Harbor, [00:18:00] he called on White to chair a national committee to aid the Allies because, you know, we just weren’t sure what should, what should the American – what should the US response be to what’s going on over in Europe.

So, uh, yes, the presidents sought him out, but it was mutual. I think he realized that having the ear of a president was a good thing for both of them. And interesting considering that he’s out here in Kansas.

Teri Finneman: And he had some of these famous guests come to Emporia, [00:18:30] right?

Beverley Buller: Oh, yes. Edna Ferber in her autobiography talks about sitting on the White’s porch. Uh, but also, Edna Ferber wrote several books based on adventures that she had with the Whites. Her book, Cimarron, which is set in Oklahoma, grew out of a trip that the Whites took her … She’d not been to Oklahoma, and they mentioned red dirt. “The dirt’s really red?” And so, supposedly the son, Bill, drove Edna, and probably [00:19:00] Will and Sallie, too, down to Oklahoma so she could see the red dirt. And this evidently the book Cimarron. And, of course, Giant was set in Texas. But her time in the Midwest informed her.

And then, yeah, Jane Addams had a sister that lived here in Kansas. They were friends with Willa Cather, who, of course, largely was in Nebraska, until she also went abroad and around the world. Yes, they had many famous people.

You know, if I may mention though to set a story straight. And I just read this again the [00:19:30] other day, a mention of Einstein visiting. There is literally no proof that Albert Einstein was ever at Red Rocks. There is a story that he had a layover. Of course, the travel back then was train, and Emporia had plenty of trains going through. But the story is that he had a layover, and so he found his way to Red Rocks. Mr. White was not home, and the housekeeper told him to please have a seat and that Mr. [00:20:00] White would probably be along shortly and could visit with him. There is no truth in that at all.

In fact, I never even found letters between the two men. They met when they both received an honorary degree at Harvard. And the famous photo of the two of them, the background honestly does look like the terrace with the door leading into the dining room at Red Rocks. And I think that’s part of where this came from. [00:20:30] But yeah, Einstein was not one of the famous people who visited Red Rocks.

Teri Finneman: In 1923, White won a Pulitzer for best editorial for a piece called “To An Anxious Friend.” What was that piece about?

Beverley Buller: Yes, that piece was another one, that I won’t say he wrote it hastily. But in “To An Anxious Friend,” he had written a letter to a friend about basically freedom of speech, that, you know what, it’s okay [00:21:00] for every person to have their say, and it’s okay to disagree. You know, don’t worry about it. That was where the anxious part came in.

And he did – White did something that he often did, he recycled that letter and made it into an editorial, not word for word, but you can compare the two, and they are quite similar. Um, and, of course, that was the Pulitzer Prize that he won in his lifetime was from that editorial.

And it’s got very quotable … [00:21:30] You know, most of his editorials have very quotable lines in them, and he chose his words … I don’t know if he chose them carefully, or if he just had an interesting way of putting words together, and, and, and sentences together, because that is another editorial. And that’s the one that won the Pulitzer. So generally when you talk about White, you talk about that one.

And, of course, that letter and then that editorial, grew out of the railroad shopmen’s [00:22:00] strike that was going on in [Emporia]. White’s friend and also fellow newspaper owner, Henry Allen, had forbid the posting of placards in business windows supporting the shopmen. And so, to test freedom of speech, White, of course, put up a placard and was kind of arrested. He … It never went to trial, never … He never was in jail. But anyway, it was a big thing. And, and then Henry Allen visited [00:22:30] Emporia, I think within the week of that editorial coming out. And people were just, you know, waiting on bated breath. You know, are the two men gonna … “Are they gonna punch each other? You know, they must hate each other.” Well, they didn’t. Henry Allen was an anxious friend, and White wrote later that, you know, “We’ll always be friends, and we have a right to disagree.” So that, that’s an interesting editorial.

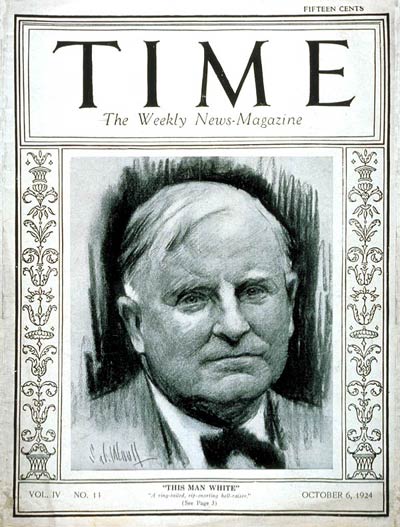

Teri Finneman: In 1924, White ran for governor of Kansas while he was publisher [00:23:00] of the newspaper. The mix of journalism and politics isn’t totally unusual, because after all, Horace Greeley ran for president. But it’s important to know why White ran for governor. Tell us that story.

Beverley Buller: Yes, and as you mentioned, it was quite common in that day. Now, we’re talking 1924. And, and even before that, it was even more common for a newspaper owner or editor to hold an office. It might be something as simple as postmaster general or [00:23:30] something.

But in that first editorial back in 1895 that I mentioned, White said, “I will hold no political office.” And he stuck to that until 1924. And being William Allen White and being so interested in politics, he was closely watching the gubernatorial race. As it stacked up, the Republican and the Democrat were both people who had [00:24:00] had ties to the Klan.

Jonathan Davis was the incumbent, and when asked, “Are you a member of the Klan?” he simply would not comment. Ben Paulen, the other candidate, would kind of hedge. He would say something like, “I’m not currently a member,” or something like that. But, you know, they were both basically denying it. But Mr. White had noticed around Emporia, there were ads [00:24:30] for Paulen in the store windows of businesses that White knew were owned by Klan members. And he waited as long as he could. In September of 1924, he began a six-week race (laughs) for governor. He made no … In the beginning, he made no effort to disguise that he … In fact, when he … He wrote an editorial called White Announces, and [00:25:00] he just comes right out and says, “I want to give Kansans a choice of a candidate who is not supported by the Klan,” or has no ties to the Klan. And he often said, “I’m not running for an office. I’m running for a principle.” And he ran for six weeks.

Oh, about a week before the election in November, all of a sudden, he had a platform. And he would give speeches. He traveled around the state. And so all of a sudden, he had a platform. [00:25:30] But he knew he would never be elected, and I feel that he threw that platform out there just to kinda see, you know, what do, what do people in Kansas think of these ideas?

I also want to clarify, because I’ve heard more than once when I’ve listened to people talking about White or writing about White, I’ve heard them mention that he ran as a write-in. He did not. He did all of the required work to be put on the ballot as an independent candidate. [00:26:00] And you had to have a petition. It had to be signed, I forget by how many. And White did that petition, but he did not circulate it in Lyon County. He circulated it outside of his county and had many, many more signatures than were required. So he was literally on the ballot.

He came in third. He later said, “I wish I could’ve come in second, but I did my …” You know, “I had my say.” And, of course, his, [00:26:30] his campaign, while not placing him in the governor’s office, did basically run the Klan out of Kansas. Because when he would give his speeches, he would ask people, “Be sure to vote for so-and-so for attorney general, and these candidates are not … These candidates are against the Klan.” They were elected or, in some cases, reelected, and so the attorney general was able to get the Klan out by saying that they were not, could not have [00:27:00] a charter. And if they did not have a charter, they could not do business in Kansas.

And, of course, there is the famous cartoon in The New York World of White running the Klan out of Kansas wearing his white suit, holding a rifle, which he did not do. But, of course, the Klan has on their white nightgowns, as he calls them, and he literally ran them … And Rollin Kirby did that, that cartoon, I should mention. And, you know, that was the public [00:27:30] view of it. And the fact that that was published in a New York City newspaper showed the impact that had. Because Kansas was not the only state back in 1924 that was seeing a scary amount of infiltration by the Klan. So White always got lots of letters. And, uh, but he got a whole lot in 1924 from people saying in other states, saying, you know, “We wanna do what you did,” and, and so on. So once again, he set a wonderful example.

Teri Finneman: [00:28:00] What do you think is White’s lasting contribution to journalism?

Beverley Buller: Oh my, so many things. You know, he left hundreds of those pithy-type editorials that I was talking about. He loved to write obituaries about people. Obviously, he wrote one for his own daughter. He wrote one for his mother. But he wrote them for the most humble people in Emporia, and wonderful, well-thought out obituaries. All of that survives. [00:28:30] Copies of every one of his letters remain and, of course, they’ve been published, some of them have … Selected letters have been published, so anyone researching him can read those letters. He won two Pulitzer Prizes and many other prizes, some awarded posthumously. His second Pulitzer was after his death. He published 22 books.

And, you know, I think he will always be associated with Kansas. [00:29:00] I so appreciate what the William Allen White Foundation has done and is doing to try to keep Mr. White out there, because so many people have never heard of him. And when they do, they fall in love with him, and they want to know more about him. And so, I’m pleased there are so many outlets to find out about Mr. White, including Kevin Willmott’s documentary about him, which is [00:29:30] now available on the foundation website. But it’s on YouTube also. So people beyond Kansas, or in Kansas, can learn about the, all of the things that Mr. White contributed to journalism that are being probably built on to this day.

Teri Finneman: White died in 1944. Uh, tell our listeners what’s become of The Emporia Gazette since then.

Beverley Buller: When Mr. White realized that he had cancer, which was diagnosed [00:30:00] up at Mayo Clinic, and he knew that he would die before the war ended, his son had been over in Europe covering the Blitz, and actually other things, too, relating to the war for the North American Newspaper Alliance. And he let Bill and his wife Kathrine, who herself was a journalist, worked in magazines, he let them know, you know, “I’m not gonna live too much longer, and you need to come back here and run the paper, if indeed that’s what you want to do.”

[00:30:30] So Bill and Kathrine moved part time to Emporia. They … And they ran the Gazette until Kathrine’s death in … I think it was 1980. So Kathrine ran it after Bill’s death. And they lived in Red Rocks, but they also maintained their apartment in New York. So they had a true dual life. They didn’t just travel the way White had. They lived in New York part of the year. And by then, [00:31:00] it was pretty easy. They had a great staff, just like Mr. White did.

So Bill and Kathrine ran the paper first. Kathrine’s daughter Barbara took over when the same situation. And I have a copy of the letter where Bill is writing to David and Barbara Walker, his daughter, to tell them, you know, “I now have the same kinda cancer my father had. And like my father, I am writing to you to see … I’m sure you don’t [00:31:30] want it, but if you would like to take over the paper, now would be the time.” So they were living in Maine at the time, and they came out to Kansas and, and worked with Kathrine to run the paper. And then after Kathrine was gone, they took it over.

Now, Barbara told me that even though her son Christopher was enrolled and actually completed his training, his college at the University of Kansas Journalism School, she never asked him [00:32:00] to take over the Gazette because she said, “I knew the pressure that my father had felt, and in a sense, that I had felt, until we realized, no, we love this paper. We wanna keep it in the family.” And so, she was so surprised and pleased when Christopher and his wife Ashley took over the paper. And they remain your … They are the face of the Gazette to this day.

Now, speaking of the face of the Gazette, it has changed. It’s hard times for journalism nowadays. [00:32:30] The building of the Gazette has now been sold. And actually, a lot of it is being done, I think, from home. And they have a small office nearby. So the Gazette building is still there, but the Gazette is not being printed and worked on out of that building. So, but it is still very much been in the White family for over 100 years.

Teri Finneman: People can come to Emporia to this day and visit William Allen White’s home. Tell us about this tourist attraction [00:33:00] and how many people visit each year.

Beverley Buller: Yes. Red Rocks, the home of William Allen White, became … Well, it was given to the state by David and Barbara Walker back in 2001. And the state went through, cleaned it out. And, of course, they left everything, which is wonderful. We have address books. We have items of clothing. We recently put a cape belonging to Sallie on display that was, had … It had been given to a family member and [00:33:30] they returned it. So we have a place to display it. So it’s almost like the Whites still live there, and they’ve just stepped out. It’s a house museum. And it opened in 2005.

It is now … Just this year, it went on the same schedule as all the other state historic sites, meaning that it is open from April to October. It is closed in the winter, although people can tour at any time of year by appointment. [00:34:00] So if somebody wants a tour for Kansas Day in January, they can call or email the site and set up a tour.

But like this time of year, it’s open Wednesday through Saturday from 10 til 5. Drop-ins are fine, but if you have an appointment, then you can be assured that you’ll get right in. Sometimes people come and a tour is in progress, so they have to wait. They have a lovely garden still, lovely porch that people can sit on. We have a visitor center. [00:34:30] I say we because I am on the board of the community partnership that runs it.

We do Sunday programming a couple of times a month this time of year. We have an annual White Christmas, tongue in cheek, event, where we have local groups. Like we might have the high school choir, or we might have a quartet. You know, local talent that entertains and people can tour the home. The Kansas State Historical Society website [00:35:00] would have all the details about visiting Red Rocks.

I’ve looked out of curiosity. Just in July, we had 234 people visit. Now, I get a program in June, and I think there were 24 people. So, that’s not even including the number of people that come to our Sunday programs. And we can have up to 50 people for our Sunday programs. So I would guess at least 1,500 people go through that site.

And I’m always [00:35:30] impressed if I visit the site for one of our board meetings, which I just did earlier this week, I like to look at the guestbook. They have an old-fashioned guestbook. And people have come from Emporia, ’cause there’s plenty of people in Emporia who’ve not seen it. But they’re coming from, you know, other states and have stopped in. One group had come from Topeka, and our site manager said, I teased him, “Did they come to eat at Braum’s?” Because there is no Braum’s [00:36:00] ice cream store north of Emporia, and people do come from probably Lawrence, too, and Topeka. And they said, “Oh no, we came to see the home of William Allen White.”

So it is a unique site very much, and we have a driving tour that people can take and a walking tour. If they go downtown, they can see some sights, like where the original Gazette was and, and where William Allen White was born. The house is long gone, but we have a lot of things that support [00:36:30] the life and the legacy of White. Both White, his wife, his mother, his father, of course Mary, David and Kathrine … uh, David and Kathrine, Bill and Kathrine are all buried out at the cemetery in Emporia. So sometimes people even tour his final resting place. But I think it is a wonderful historic site for our state and still a beautiful home and still very much full of history.

Teri Finneman: And then our final question of the [00:37:00] show is, why does journalism history matter?

Beverley Buller: Well, going back to my first question. Journalism history matters because we need to inspire young people to pursue careers in journalism. And by looking at the history of it, the people who contributed to journalism, it can be a wonderful thing and can provide a lasting career. People [00:37:30] often don’t stay in careers as long as William Allen White did. I personally was a teacher for 40 years, and that’s probably (laughs) unusual in this day and age. But the wonderful thing about a career in journalism nowadays, it evolves so much. We’re doing a podcast. That’s part of journalism nowadays. So you might start in one area and you have a lot of flexibility. You have flexibility that William Allen White did not have.

You know, toward the end of his life, he was [00:38:00] able to do broadcasts from his study through CBS. But, you know, that was pretty much it. So a career in journalism, you can … It’s important and inspiring to learn about the history of it and all of the wonderful people who came before. But a career in journalism nowadays can just be multifaceted, and honestly, it’s more important than ever.

And, and people need facts. And I was a librarian for years. Tried to teach [00:38:30] children, just because you read it on the internet does not make it true. Well, if they read it in a newspaper, and I want newspapers to continue, it should be considered … It should be … Newspapers need to be trustworthy. And boy, is William Allen White a good example of, of doing that. But yes, it is so important to study the history of journalism.

Teri Finneman: All right. Well, thanks so much for joining us today.

Beverley Buller: Thank you.

Teri Finneman: Thanks for tuning in, and be sure to subscribe to our podcast. You can also follow [00:39:00] us on Twitter at @JHistoryJournal. Until next time, I’m your host Teri Finneman signing off with the words of Edward R. Murrow, “Good night and good luck.”

Photo: Time cover featuring William Allen White, Oct. 6, 1924. Image courtesy of the Emporia State University Archives