2025-6| Download PDF

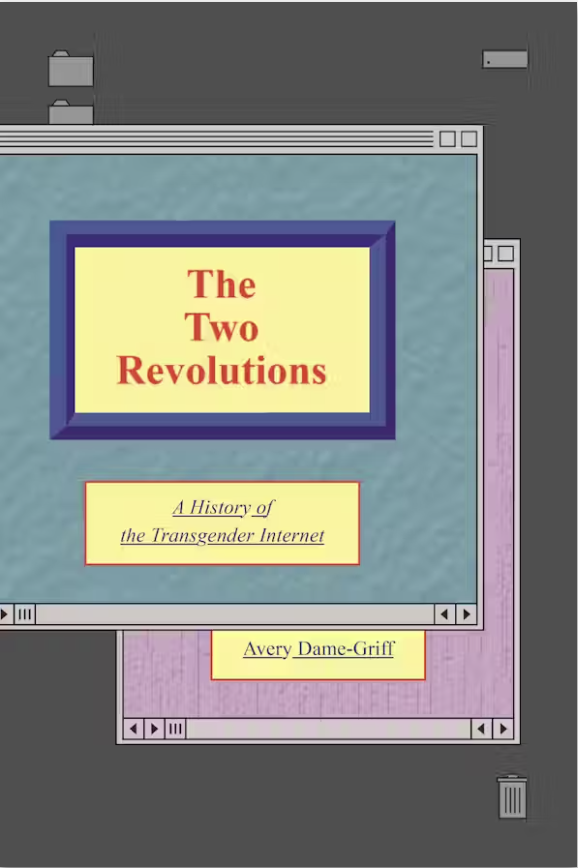

Dame-Griff, Avery. The Two Revolutions: A History of the Transgender Internet. New York, NY: NYU Press, 2023, 272 pp., $32.00 (paperback). ISBN: 9781479818310. Reviewed by Larissa Little, Department of Communication and Journalism, University of Maine, larissa.little@maine.edu.

The transgender community existed long before the rise of the internet. Yet the world wide web and social media transformed the trans community in evolutionary ways. Avery Dame-Griff’s The Two Revolutions chronicles the historical developments of two revolutions – one technological, the other social – that intersected to influence the growth and shape of the contemporary transgender community.

Before the internet became ubiquitous, transgender people communicated with each other through community periodicals that developed national newsletter exchange networks. These newsletters connected transgender people, fostered community and informed about resources. But newsletter distribution could be risky, as “scandalous” mail might compromise its recipient. When personal computing and Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) emerged, sites such as GenderNet allowed users to log in anonymously and receive much of the same support and connection.

As Dame-Griff explains, the development of America Online (AOL) in the early 1990s created new community connections outside of the original BBS forums. Transgender users began to advocate for their online visibility and presence, and by 1994 AOL’s Terms of Service evolved to allow TV (transvestite) Chat and gender community terminology. “In the Gazebo [chat room], users felt comfortable coming out and seeking support; for some, being able to chat online gave them the courage to seek out in-person support groups,” notes Dame-Griff, adding that “Trans users… had the lowest churn rates, prompting AOL executives at one point to request a meeting with TCF [Transgender Community Forum] manager Smith to discuss how she’d managed to successfully retain users… she knew, of course, [that] TCF offered support and acceptance to a population that sorely needed it” (p. 76).

Once transgender people had fostered stabilized digital communities, AOL (and other) forums exploded with discourses over identity. Groups on early social media sites, like Usenet, had previously suffered so-called “flame wars” that might last weeks. Regular posters in these trans groups ended up turning them into their own discursive spheres that created neologisms such as “cisgender.” Today, cisgender (meaning one who identifies with their assigned birth) may be a common word, but Dame-Griff details its origins in massive online arguments occurring in the late 1990s. Transgender users and groups leveraged flame wars and other rhetorical tactics to assist in their coming to terms with their identities while developing transgender community social norms.

By 1996, the development of the world wide web freed users and communities from chat rooms operated by commercial media corporations. New web pages and profiles encouraged users to play with the idea of self-fashioning their online presence in new ways. New platforms began to emphasize visual imagery, adding new dimensions to identity formation. “Tumblr’s emphasis on image sharing gave trans users a platform for visualizing and eroticizing the trans body, including bodies that were left out of the mainstream representation or that failed to meet normative standards of attractiveness,” Dame-Griff explains (p. 176). Tumblr’s affordance of tagging posts helped establish new social norms as posts tagged with #trans or #transgender naturally began to proliferate and help users find community.

The Two Revolutions also details the constrictions of technology (through search engines and algorithms). These systems prioritize medical models of gender transition when someone searches online for transgender content, reinforcing the limited idea that to be transgender is to medically transition from one gender to another. Such algorithmic channeling limits autonomy while providing limited and selective information. Dame-Griff argues that although online visibility has brought the transgender community further into mainstream media, which has increased its access to resources, it has also exposed that same community to new risks when social media’s corporate owners can manipulate online presence and activity. Dame-Griff concludes that trans people need to own the platforms they use to build community in service of protecting trans histories and knowledge.

The primary source research supporting Dame-Griff’s conclusions includes reviewing decades of periodicals and webpage archives. The evolutionary relationship from newsletters to forums are detailed effectively, and the computing-generated language innovations are made clear. For example, The Two Revolutions shows how when trans people communicated primarily through the mail, the community primarily consisted of crossdressers and transvestite women, but when people could communicate immediately via social media, new words like “transgender” and “genderqueer” became common, and trans men and non-binary people found their place among the community.

The Two Revolutions offers an incisive and detailed analysis of the evolutionary and developmental relationship between the transgender community and new technologies. Dame-Griff’s book provokes questions in the reader’s mind about the ongoing relationship between technology and trans community development, such as how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and virtual reality will further transform identity and community. In each case, as The Two Revolutions makes clear, there will be exciting new affordances and opportunities but also the threat of channeling and circumscription for trans users. The book is very well-written, and evidences Dame-Griff’s deep knowledge with contemporary communication practices in the trans community.

The Two Revolutions provides vital history to an understudied subject, as many people remain confused about where and when trans identities emerged. When Time magazine proclaimed the “Transgender Tipping Point” in 2014, it represented a moment in time about visibility, but, as Dame-Griff points out so well, trans people have always existed, have always sought community and have been carefully crafting their identities for decades before 2014. The Two Revolutions is a must read for anyone interested in transgender scholarship or queer histories, because it provides vital historical information about an important but understudied contemporary social phenomenon.