2025-1| Download PDF

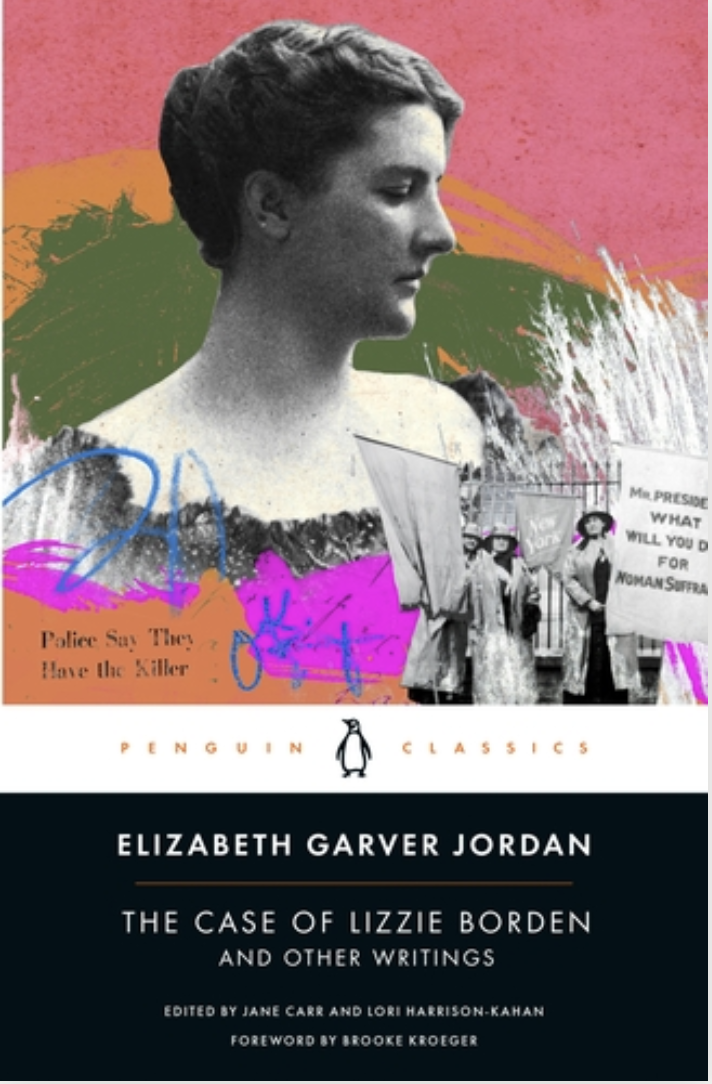

Jordan, Elizabeth. Jane Carr and Lori Harrison-Kahan (Eds.) The Case of Lizzie Borden and Other Writings: Tales of a Newspaper Woman. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2024, 432 pp. $22.00 (Paperback) ISBN 9780143137603.

Reviewed by Bailey Dick, Bowling Green State University, School of Media & Communication (bdick@bgsu.edu)

In a January 1899 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, Elizabeth Garver Jordan suggested that women who aspired to a career in journalism undergo “a severe self-examination,” (p. 128) guided by the following three questions:

1) Have I the brains for newspaper work, with the education and mental training which will enable me to attain success in a profession that is so exacting?

2) Have I the health to withstand the long hours, the nervous strain, the effects of irregular meals, and the frequent attacks of physical and mental exhaustion incidental to the life of the reporter?

3) Have I the character and dignity which will win the respect of my fellow-workers and hold that respect for all time; can I work among men on the footing of common interest and good fellowship, with no tears, no flirting, no affairs, no questions of sex?

Jordan describes the hardships of an early career for young women journalists: decrepit apartments, living paycheck to paycheck, the unreliability of a “free lance” career, and covering “flower and cat shows…and an occasional turn at book reviewing,” (p.130) after proving her ability to “write her stories without the ‘feminine touches’ so dear to her heart during those peaceful days on her hometown press” (p. 133).

The life Jordan describes could be one of a young, female journalist today—a common refrain readers might notice as they make their way through “The Case of Lizzie Borden and Other Writings: Tales of a Newspaper Woman.”

The curated selection of Jordan’s long-out-of-print newspaper, magazine, fiction, and editing work are given new life here, contextualized by a foreword by Brooke Kroeger, along with an essay by editors Jane Carr and Lori Harrison-Kahan at the beginning of each of the book’s four sections. There are multiple layers of effort by Carr and Harrison-Kahan to make Jordan and her writing relevant to present-day readers, from their selection of works, to describing Jordan as a “proto-influencer,” to drawing connections between Jordan’s writing and current debates in the field about objectivity, subjectivity, and activist reporting. Jordan knew, as the editors note, how to “mobilize print culture as a means of literary activism” (p. xix). The four editorial notes do not overshadow Jordan’s own writing, but instead provide useful historical and journalism-specific context for non-scholarly readers of this Penguin Classics title.

Four of the twenty-nine pieces of Jordan’s writing contained in the text are devoted to the Lizzie Borden murder trial—prime examples not only of early true crime reporting, but Jordan’s highly literary, narrative style that focused on humanizing characters, particularly women. In Jordan’s coverage of the Borden trial, there are echoes of how the press covers so many high-profile trials. “There are two Lizzie Bordens. One of them is the very real and very wretched woman who is now on trial for her life in the little courthouse at New Bedford, Mass.,” Jordan wrote in a dispatch for The New York World. “The other is a journalistic creation skillfully built up by correspondence and persistently dangled before the eyes of the American people until it has come to be regarded as a genuine personality” (107). Jordan’s analysis is sharp, preceding media scholars, true-crime podcasts, and cable television by a century.

Jordan also had her thumb on the reality for women living and working in an inherently patriarchal world—one wrought with physical, carceral, economic, and relational violence. As the term “sexual harassment” wasn’t coined until the 1970s and transparent discussion of sexual violence in news outlets could very well have been stifled by the Comstock Act, Jordan turned to fiction to tell stories of the harassment women faced in their daily lives. In a serialized version of “Tales of the City Room” published in Scribner’s, woman after woman is failed by the men in their lives. In “A Romance of the City Room,” there’s reporter Miss Bancroft, who receives a year’s worth of roses and unsigned letters from an obsessive co-worker who later dies of consumption. The titular character in “Miss Van Dyke’s Best Story” returns to work after reporting an election night special in the city’s red light district to find that her male colleagues have created a cigarette- and beer adorned shrine on her desk to her, “the tenderfoot of the tenderloin,” as they crowned her. “I wrote a faithful report of what I saw, and that is all there is to it,” she tells her editor, but the torment went on for months. There’s Ruth Herrick, who interviews and befriends a woman charged with murdering her abusive husband, but ultimately decides against publishing her story to protect her. For Jordan, as Carr and Harrison-Kahan describe it, “emotion and human interest were pathways into insight about the new and the stories that most headlines left untold” (p. 2).

“The Case of Lizzie Borden and Other Writings” makes archival materials and examples of pioneering women’s reporting accessible for a wide audience and easily makes clear the connection between the patriarchal past and present. We academics might miss some of the hallmarks of academic texts like on-page footnotes or sample artwork from the archival materials themselves. But a paperback, mass-market book like this one is sure to appeal to true-crime afficionados and journalism historians alike.