2024-11| Download PDF

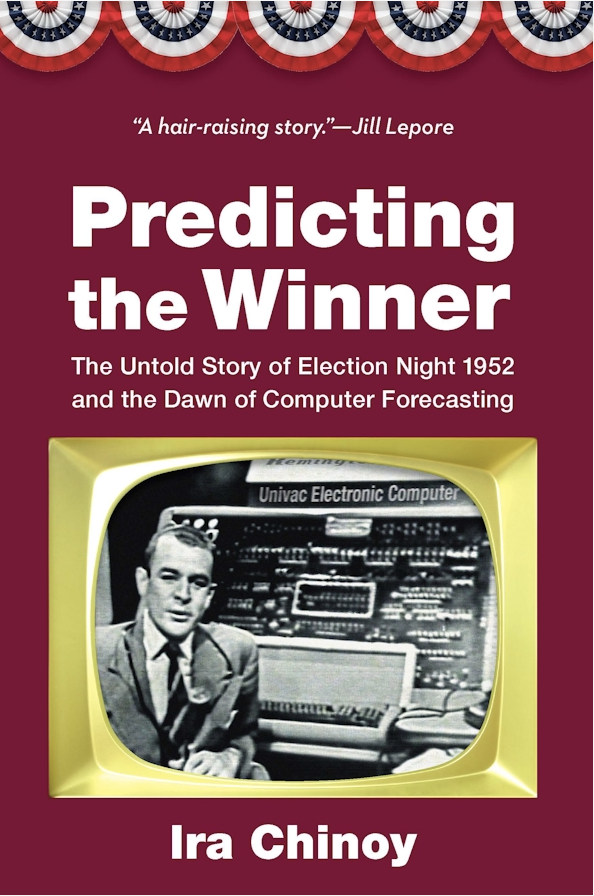

Chinoy, Ira. Predicting the Winner: The Untold Story of Election Night 1952 and the Dawn of Computer Forecasting. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2024, 384 pp., $38.95 (Hardcover). ISBN: 9781640125964

Reviewed by Pam Parry, Department of Mass Media, South East Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, pparry@semo.edu

The 1952 presidential election altered the American landscape forever. Journalists leveraged the burgeoning fields of television and computer technology in order to gain a competitive advantage in forecasting the results. General Dwight Eisenhower also sought advice from Madison Avenue and featured himself in spot advertising, changing the way candidates would run for office. He understood the power of advertising and television, and he used them skillfully. Scholars have studied his use of advertising and televsion, but author Ira Chinoy spent more than twenty years researching it for another transformative reason—journalism’s efforts to accurately predict elections utilizing specialized computers. In addition to describing the events that occurred seventy-two years ago, he connects them to democracy today and explains why this event still matters in the twenty-first century.

In Predicting the Winner, Chinoy posits that November 4, 1952, “changed profoundly” the history of elections in the United States (p. 1). It not only changed advertising, television, and public relations, but it also impacted journalism. “This is the untold and timely story of a critical pivot point in American politics, journalism, and culture” (p. 5).

Accessing twenty-five archives, the author described his “treasure hunt” for this account as “the only exploration of election night 1952 to piece together the television broadcasts from CBS and NBC—thirteen hours combined” (xi-xii). In fact, Chinoy’s meticulous research is one of the book’s greatest strengths. The author explains the importance of election nights throughout American history and the role journalists played in covering them. With the new medium and the expanding computer field, journalists embraced available technology to predict the election between Eisenhower and Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson.

But the prospect was risky.

In 1948, the press was embarrassed and had their credibility called into question when The Chicago Daily Tribune and other outlets wrongfully predicted Thomas Dewey would defeat incumbent president, Harry Truman. They could not afford to get it wrong (again), and no one had ever used computers to predict the outcome of an election as it was unfolding on television. Chinoy described the tension and drama of the night as exciting. The book’s ten chapters discussed the history of presidential election coverage, indicated the times predictions have failed, and set the stage for how the 1952 story unfolded and impacted future reporting.

This book contributes to the historiography of political campaigns, journalism, television, culture, computer technology, and presidential history. As such, it would be good to assign for graduate courses in these fields or combining them for an interdisciplinary offering. This book would also be good for scholars and experts who want to learn about the evolution of election night forecasting and the technology—from the telegraph to the advanced computers of the twenty-first century—that journalists have employed to conduct them. Political journalists would benefit greatly from reading this work.

Predicting the Winner is well-research and well-timed in providing applications to modern-day elections, including the contentious election of 2020 and how Americans can improve their democracy. Chinoy discusses the ways in which computers can enhance coverage, but he also quickly points out the flaws in relying upon computers. For instance, despite the mechanization and accuracy of computers, flawed data could result due to human error. Humans had to enter the data, and humans had to interpret the data. So, journalists can employ computers in election coverage, but one problem that still exists is the potential for operator error.

Additionally, Chinoy does a masterful job of answering the “So What?” question. In other words, he has researched and analyzed a treasure trove of primary and secondary sources about an event that occurred seven decades ago, but he convincingly conveys to the readers why they should care about this event today. He pointed to the 2020 election and the January 6 uprising that followed, positing that election nights are consequential and the public has to be able to trust the credibility of the news, as well as other levers of democracy.

Would the computers employed in 1952 have been able to predict that the forty-sixth president of the United States would withdraw from the 2024 race just months before the election?

Probably not, but Chinoy is correct that the adventure is thrilling.