2024-6 | Download PDF

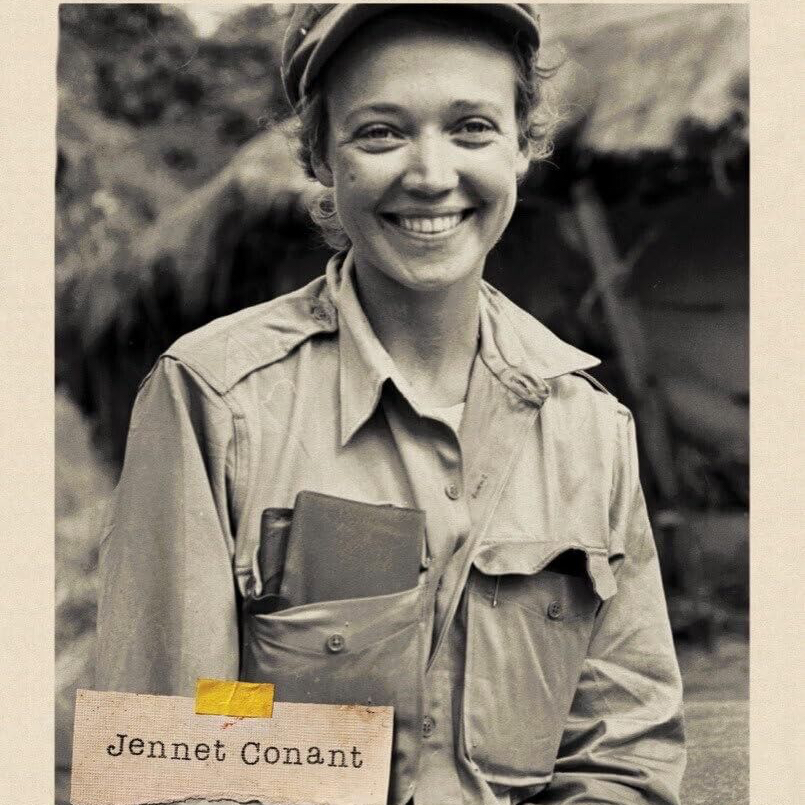

Conant, Jennet. Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins. New York New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2023, 416 pp. $32.50 (hardback). Reviewed by Paula Hunt, Independent Scholar, pdhunt27@icloud.com

Marguerite Higgins arrived in Europe in late 1944 as a 24-year-old cub reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, determined to be a foreign correspondent. She made her name covering the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp in 1945 and reported on the Nuremberg trials and the Berlin airlift. By 1947, the war was over, and Higgins, at just 26, was already Berlin bureau chief. It was a stunningly quick rise but long enough to earn Higgins a reputation among the press corps for sharp elbows, ruthlessness, and a propensity for using sex to get information and gain access to newsmakers.

She was, some would also admit, a pretty good reporter too.

Throughout her 24-year career, Higgins became one of the most famous women journalists in the United States, establishing her name by reporting on foreign affairs and from war zones in Europe, Indochina, and Vietnam. In 1951, she was one of six reporters — and the first woman — to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting of the Korean War. At a time when women were routinely relegated to covering the four Fs — food, family, furniture, and fashion — Higgins battled publishers, editors, her peers, and the military to be on the front lines of major world events. She screamed, threw fits, and made threats to get what she wanted (better pay, a prime assignment, and a fellow reporter sidelined).

Born in Hong Kong in 1920, Higgins grew up in Oakland, California, and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, with a degree in French. But writing for the student Daily Californian was her real passion. In 1941, she was one of 11 women admitted into Columbia University’s master’s program in journalism, which at the time capped the number of women it allowed to enroll. Her stint as a campus correspondent for the Tribune while at Columbia led to her being hired as one of its first female news reporters.

While Higgins had many critics, few questioned her ferocious work ethic or the furious pace she drove herself. She was named the Tribune’s Tokyo bureau chief in 1950 and established its Moscow bureau in 1955. She interviewed prominent political figures like Francisco Franco, Marshal Tito, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Chiang Kai-Shek. When the Tribune dropped her syndicated column in 1963, she moved to Newsday, where she wrote on domestic and national affairs three times a week. She became a popular public speaker that, along with her column, book projects, and magazine assignments, further enhanced her fame. But the unrelenting grind also affected her health, which had become increasingly compromised due to bouts of dysentery, malaria, and bacterial infections that she likely contracted during her many reporting trips to tropical countries. Shortly after returning from a trip to Vietnam in 1965, she was diagnosed with leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease transmitted by the sand fly, leading to her death in 1966 at the age of 45.

Fierce Ambition is a quick read that will appeal to students interested in the story of a single-minded woman who pursues stories despite the many obstacles she faced during her career in a male-dominated field. But in attempting to match the tempo of Higgins’ fast-paced life, Fierce Ambition sacrifices meaningful scrutiny of the knotty contradictions in Higgins’ character or allows for any pause to step back to contemplate the political, economic, and social forces that informed the domestic and international scenes at the time she was writing. Cliches, sweeping generalizations, and oversimplifications replace insightful explanations. “After the permissive war years, the country had become more prudish” is not a satisfactory description of American mores in 1954 (p. 256).

Fierce Ambition’s laser focus on Higgins’s personal and professional life suggests she was an anomaly. Although some women journalists make an appearance — Martha Gellhorn, Ann Stringer, photographer Margaret Bourk-White—students could be excused for coming away with the impression Higgins was a singular figure when nearly 120 women were accredited as correspondents during World War II. Although most of them never made it to the front like Higgins did, they pushed boundaries, endured scorn, and earned respect for their reporting before she arrived in Europe. At the same time, Fierce Ambition will disabuse students of believing there was such a thing as a journalistic sisterhood standing shoulder to shoulder against male hegemony. Higgins was notably hostile toward other women journalists throughout her career., and they generally had nothing good to say about her, either.