For the 86th episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Nick Hirshon spoke to John Maxwell Hamilton about the propaganda spread during World War I by President Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Relations.

For the 86th episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Nick Hirshon spoke to John Maxwell Hamilton about the propaganda spread during World War I by President Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Relations.

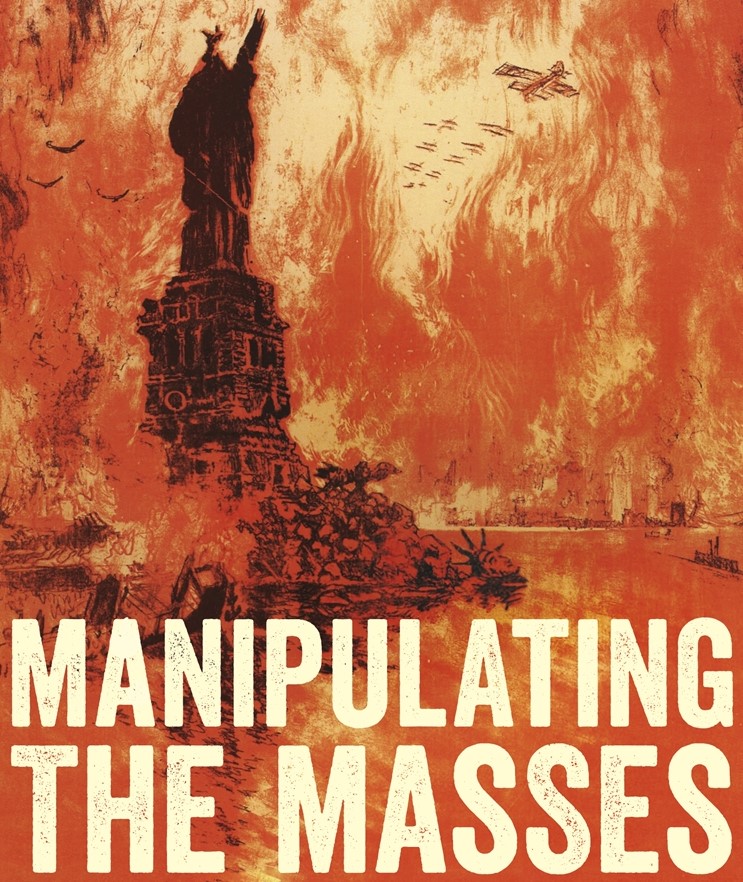

John Maxwell Hamilton is the Hopkins P. Breazeale Professor of Journalism at the Louisiana State University Manship School of Mass Communication and a global scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. He received the AEJMC History Division’s 2021 Book of the Year Award for Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda (LSU Press, 2020).

Transcript

John M. Hamilton: And total war requires propaganda to get people to do what you want them to do, and that’s the turning point.

Nick Hirshon: Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to reexamine the stories you thought you knew and the ones you were never told.

Teri Finneman: I’m Teri Finneman, and I research media coverage of women in politics.

Nick Hirshon: And I’m Nick Hirshon, and I research the history of New York sports media.

Ken Ward: And I’m Ken Ward, and I research the journalism history of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Nick Hirshon: And together we are professional media historians guiding you through our own drafts of history. This episode is sponsored by Taylor & Francis, the publisher of our academic journal, Journalism History. Transcripts of the show are available online at journalism-history.org/podcast.

One week after the United States entered –

[0:01:00]

World War I in April of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information. It marked the first and only time the United States had a ministry of propaganda. The committee tried to shape American views and attitudes through its own national newspaper, posters that were plastered on buildings and displayed in storefront windows, pamphlets distributed by the millions, textbooks and church sermons, and even feature films and talks during intermissions, and it created a pioneering new service to transmit Wilson’s idealistic rhetoric to foreign audiences, distributing movies, setting up public affairs offices in conjunction with embassies, and testing techniques for dropping leaflets in enemy territory by air. The committee was dismantled when the Allies emerged victorious, but its blueprint endures in the information state that exists today in peacetime as well as war.

[0:02:00]

On this episode of the Journalism History podcast, we examine the legacy of the Committee on Public Information with John Maxwell Hamilton, a journalism professor at Louisiana State University.

Well, Jack, thank you for joining me today. We’re here to discuss your book, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda, published by Louisiana State University Press, and you tell the story of the enduring threat to American democracy that arose out of World War I through what you call ministry of propaganda, the Committee on Public Information, and you’re here today because Manipulating the Masses was selected as the winner of the book award that is given annually by the History Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, which sponsors this podcast. So, first off, congratulations on that honor.

John M. Hamilton: Thank you very much. I appreciate that.

Nick Hirshon: And as we start this conversation, obviously in the title of your book it says the birth of American propaganda. I find that very provocative because I think a lot of people, if they know anything about propaganda, might –

[0:03:00]

associate it with a foreign country, a dictatorship. So can you first just give us your definition, what is propaganda?

John M. Hamilton: So there are a lot of ways to define propaganda. It’s almost always today seen as being pejorative, that is a negative, a negative idea of trying to manipulate what people think. A simple definition would be something like an effort to try to get people to think what you want them to think. Uh, antecedents to that, of course, have existed for a long time. It’s not like propaganda just started in the 1914, although the word itself became a brand new word in World War I. Encyclopedia Britannica did not have an entry in its 1911 edition for propaganda, other than to mention that the Catholic Church had a college of propaganda for the faith. At the end of the war, it had a ten-page definition and that definition was written actually by a British propagandist, and it’s one of the best definitions –

[0:04:00]

I’ve ever seen. It goes like this. Those engaged in a propaganda may genuinely believe the success will be an advantage to those whom they address, but the stimulus of their action is their own cause. The differentia of a propaganda is that it is self-seeking, whether the object being worthy or unworthy intrinsically or in the minds of its promoters. It’s, it sounds like, sounds a little complicated perhaps, but it’s a good definition because it makes the point that propagandists want to get, want you to think what they want you to think, and they believe it’s very important for you to think what they think, rather than honoring the democratic process, which would be to give people facts so they come to their own conclusions.

Nick Hirshon: Sure. Well, thank you for going to those lengths to give us the full definition because I feel like propaganda is a word that has a negative connotation, again maybe associated more with, as we grew up as American schoolchildren hearing about other countries using propaganda in a political sense. Then when we realize, well, actually propaganda is all around us, maybe all the time used by many different –

[0:05:00]

forces in certain ways. And I want to start by, in your book, you mention the legacy of propaganda before World War I at least a little bit, how politicians were preoccupied with public opinion since the beginning of the democratic experiment in the United States, and presidents had occasionally taken direct action to curb unwanted news and views. In 1798 John Adams signed Sedition Acts to criminalize any expression that brought the United States, the president, or Congress into, quote, contempt or disrepute, and during the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln authorized the secretary of war to take control of the telegraphs and stop news stories. In the run-up to the Spanish-American War, William McKinley sought to better manage the press by increasing the number of White House news releases. So what can you tell us about these efforts to stifle political speech in this country before Woodrow Wilson?

John M. Hamilton: So couple of things that need to be said there, Nick. First of all, propaganda has two parts to it. One part is the provision of information, the things you want people to know, and the other is the suppression of information, things you don’t want them to know because if they know it –

[0:06:00]

they might not think what you want them to think. In other words, you don’t want them to have inconvenient information that is inconvenient from your point of view as the propagandist. There’s always been propaganda. Every time a king put on an ermine, ermine robe, they were conducting propaganda because they were adding a luster and authority to their own words and actions. So that’s not a new concept, even if the word didn’t exist before. Uh, what changes in 1914 is that we had, with World War I, is that we had pervasive, systematic propaganda for the first time, where it was truly institutionalized. Now, this would have happened without the war eventually for a couple of reasons. First of all, the rise of mass media meant that all of a sudden people could come up with ideas of their own, and governments had to interact with that or react to that by finding ways to use those communication mechanisms to get people to think what they wanted them to think. And of course all politicians are engaged in persuasion. That’s, that’s –

[0:07:00]

that goes with the job, and it’s actually a good thing, not a bad thing, but there are many pernicious ways of using information or subverting the mass media. But the mass media existed already, and that made it inevitable we would have propaganda, systematic, pervasive propaganda as I call it. Uh, the war accelerated the process because now we had a total war in which everybody in the country — in these countries involved had to be mobilized. And the state became much bigger in World War I in all the countries, you know, and started worrying about when, when a soldier was wounded, and millions were, who would take care of them? Would the state take care of them? They had to make sure that they could make adequate armaments. They had to make sure people were conserving food or signing up for the conscription. Uh, so it was – and this is not my term. It’s a common term to use for World War I. It was total war, and total war requires propaganda to get people to do what you want them to do, and that’s the turning point. Not that there wasn’t anything before that resembled propaganda, but that –

[0:08:00]

all of a sudden it was happening on a scale that was unprecedented.

Nick Hirshon: And I found interesting in your book the connection between Woodrow Wilson’s second campaign for president and the CPI. So Wilson ran for a second term in 1916 against the Republican Charles Evans Hughes with a campaign message of he kept us out of war. Uh, it’s kind of ironic ’cause then Wilson’s going to get into war shortly into his second term. But he won by a slim majority in the Electoral College by sweeping the solid South and winning several swing states by small margins, and then he established the focus of your book, the Committee on Public Information, on April 14, 1917, one week after the United States entered World War I. It was to be composed by the secretary of state, secretary of war, secretary of the Navy, and a civilian who would have, quote, executive direction of that committee. The initial concern with the committee was to censor news that could compromise military action, but Congress had not passed any laws governing that. No one had spelled out what information that committee would provide. So what do you see as this connection –

[0:09:00]

between Wilson’s 1916 campaign and how it became, as you said, an incubator for the CPI?

John M. Hamilton: This question is a good one for people who are historians because it, it raises a — it’s a good example of what, what you should do as a good journalist or a good historian. Uh, actually I think of myself as a journalist who uses historian, historians’ techniques. So my initial idea was that the phrase “he kept us out of war” was cynical. It was a good example of over the top propaganda and so I wanted to check it out, and when I did that, I found an unpublished memoir in a large stash of papers that belonged to Robert Woolley, who headed the Democratic National Committee Publicity Bureau. And as I began to read, I realized that there wasn’t that, that phrase wasn’t being used cynically by Wilson. He actually hoped there, we wouldn’t get into war.

[0:10:00]

He did, however, know that it may be inevitable to go to war, and he was somewhat uncomfortable with the phrase because it could be seen as cynical, and, and Republicans hated that phrase and held it against him forever afterwards because they thought it was misleading. But it, but it turned out to be a little bit more complex. You know, in today’s age where everybody tries to find the worst thing about their opponent and, and no gradations, it doesn’t really fit the bill as an utterly cynical effort. But what did come out of it, as I learned, was that the Committee on the Committee on Public Information was really a function of or grew out of the Democratic National Committee Publicity Bureau. And that’s very interesting to me because it reveals some, some important aspects of propaganda. The first is that you could argue, I believe, that Robert Woolley actually carried the day for Wilson. You can’t pick any one factor. I mean you could even argue that Charles Evans Hughes, who was Wilson’s –

[0:11:00]

uh, adversary in that campaign, lost because he had a beard. There’s never been a candidate with a beard ever since. And, you know, if, if Hughes had actually shaken the hand of the governor of California, he probably would have – and he forgot to do it. He didn’t do it because he was badly — he was badly managed when he was in California. If he had shaken that guy’s hands, Hiram Johnson, he probably would have gotten the 3,000 more votes he needed in California. He would have been president. But Woolley is very important to the Democratic National Committee, and it was the best campaign that had ever been run from a publicity point of view up to that time, and there were some new techniques that were used but it was also just very clever and systematic use of the information tools that they had. And so — and in addition to that, a number of the people who worked in the campaign in the Publicity Bureau went on to be people who were in the CPI. The number two person in the — in the campaign was George Creel, and he went on to be the head of the Committee on Public Information. So what comes out of this is both an understanding of the evolution of the –

[0:12:00]

Committee on Public Information, where it come, comes from and its antecedents, but also a second point, and that is that political campaigns and governing have something very much in common. How one runs for office often translates into how they govern when they are in office. You can look at that today with Obama. He’s the president, was the first president to use social media, and then what does he do? He sets up a social media office that’s bigger than the press office, had 24 or 25 people, more people than were in the — his own press office when he becomes president. You look at Donald Trump. He’s the Twitter president. And what does he do when he comes to the White House? As we all know, he Twitters to a fare-thee-well. So there’s an example of you thought you were looking for something else but, but became curious, and that curiosity leads you to a conclusion that you had never expected to find.

Nick Hirshon: Mm. And it’s fascinating. As we go through this conversation, I know there’s a lot of what you see as antecedents in, you know, CPI, you know, coming to bear in the years later. Um, so –

[0:13:00]

as we get into some of the men and women who were chosen to run CPI – and it’s interesting, the women here. The civilian chairman was a man named George Creel, who you describe as energetic and creative, impulsive and mercurial, and you say that before Washington pundits had coined the term “spin” they referred to it as “Creeling,” and I thought that was fun. And you mention some of his failures in the book. For example, he had insisted that the CPI be in charge of field propaganda against enemy military forces, and then failed to mount a serious effort, but you also credit him with being ahead of his time in hiring women for senior positions. So what can you tell us about the rather complicated legacy of George Creel?

John M. Hamilton: Well, first I would say this. Creel was a terrible choice for the job. Uh, we had never had, well, we never had and never again had a ministry of propaganda, although all of the CPI functions lived on but in a more fragmented way. The CPI, everything that happens today can be traced in some way or other, even social media, to the CPI. Creel –

[0:14:00]

was a born propagandist. He was a muckraker, but he belonged to that school of muckraking which was always hyperventilating, and Creel was much more interested – in many ways he’s kind of like Trump, much more interested in making an impression, you know, than he is in utter fidelity to facts, and so he could be very tendentious and very irascible. So in private he was — he was well liked and was funny, but once he got on a platform, began to speak, or once he was in his public role, he ended — ended up being far too edgy. And, and because this was such a brand-new activity, having somebody in it who was so — just by his very method of living was so controversial, it actually made the CPI’s job more difficult and gave it a bad, a worse reputation than it, that it should have actually had. And had somebody like Robert Woolley run it, the guy who was at Democratic National Committee, it would have been a much better choice because he was both highly creative but knew how to moderate himself and modulate what he did. Creel didn’t have that.

[0:15:00]

And so that, that’s part of Creel. The other part was he was wildly energetic and, and very creative, and that could be good, and we can see some good things he did as a result of that. But he was also a terrible manager, and so the CPI was so chaotic that at the end of the war, the Council on National Defense was put in charge of dismembering the organization and trying to figure out what happened. They couldn’t even — they couldn’t even sometimes, hard as it is, hard as it is to believe, they couldn’t even be sure how many different units there were because they were changing all the time, once as a unit does something else, and they couldn’t actually fit it all back together again, which tells you something about the chaos that characterized Creel’s stewardship of the organization.

Nick Hirshon: Sure. Well, and can you just briefly touch on the fact that he was hiring women for senior positions? Was this unusual at the time, or how did that come to be?

John M. Hamilton: Yeah. He was — he had been very strong in the suffrage movement and had actually been engaged in it.

[0:16:00]

Uh, his mother had been a strong-willed woman and the father had not been a very together father and had his own problems, so the mother really ran the family. And Creel admired that, we know from what he said. And then later on he was — this was a cause that he really believed in, especially the New York suffrage movement where he, where he, where he actually helped a woman named Vira Whitehouse, who’s one of the heroes in this book, who can be credited with actually getting the vote for the women in 1917. Everybody thought New York would not succeed in getting a statewide suffrage positive vote for suffrage, and she did. She’s an extraordinary woman. So Creel, Creel was actively engaged in that. Another woman that he brought in – I’ll come back to Vira Whitehouse in a minute, but another women he brought in was Josephine Roche, who he hired. For a brief period, he was the police commissioner in Denver. He had been an editorial writer, and he kept his job as editorial writer, became a police commissioner –

[0:17:00]

which by the way most, most people don’t think journalists should do both, but in those days that wasn’t, that wasn’t clearly an ethical issue like it is today. And he was very speedily fired because he was just too outspoken and unpolitic and so forth, but he hired her to work with prostitutes and others trying to clean up the city. Uh, and, and she’s an extraordinary woman who went on to be in the Roosevelt administration, Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, did some wonderful work in mining, in family-owned mines, and she came to work for Creel working on immigrant issues, and she did some very good things there. Vira Whitehouse, who was — came from a very wealthy family – her husband was very wealthy – and was beautiful – uh, there were stories in the New York Times saying she was the most beautiful woman in New York – was also very, a very, very good manager, and after that suffrage vote in 1917, Creel had decided he wanted to start doing propaganda overseas. The first months had been strictly domestically.

[0:18:00]

And she said she wanted to do that, and so he gave her the job to go to Switzerland. And of all the commissioners overseas, and many of them had very difficult jobs because the embassies didn’t want anything to do with what we now think of as public diplomacy, the idea of reaching common people on the street. They thought that was déclassé and not something you should do. Uh, but they particularly didn’t want a woman doing it, and there were no foreign service officers who were women, and against great odds and opposition she did an excellent job and probably, arguably did the best job of any of the CPI commissioners overseas. And to Creel’s credit, even though this process overseas was exceptionally poorly managed, I mean it probably has reached the point of his worst management area was the overseas stuff, he can be credited with inventing public diplomacy, and that’s a — that’s an achievement.

Nick Hirshon: It’s pretty incredible, and I know you’ve been getting into some of the personalities that you’ve included in the book. Uh, another member of CPI that might –

[0:19:00]

be familiar to listeners of this podcast was Edward Bernays, who’s often considered the father of public relations. I know you don’t spend a lot of time on him in the book, but I did want to mention that we covered his career extensively in Episode 51 with Shelley Spector of the Museum of Public Relations, and in Manipulating the Masses you describe how Bernays saw the CPI as, quote, a pioneer effort with trial and error with much fumbling. And you’ve kinda given us that impression right now about some of the inconsistencies of George Creel, but any nuggets that you can tell us about Bernays and the CPI?

John M. Hamilton: Well, yeah, maybe two things. First of all Bernays had been, fallen into that category of PR person that was more like a theater publicist coming up with stunts to get somebody to go to the theater. And the, the experience of World War I, he came out the other end of that much more oriented toward what we would call today public relations, and, and as you, many people who are listening to this podcast know, he –

[0:20:00]

he’s credited with inventing the term “public relations.” Um, or public relations council. I mean there’s different ways he said it. And he didn’t have that big a job in the CPI. He’s remembered because, of course, he became so important later and he wrote a lot about it, but he wasn’t the most, the most significant person in the CPI by any means. But the second thing I would say is there were a number of people who worked in the CPI who are today remembered as the pioneers of public relations. And I really – didn’t work in the CPI, but he worked with the CPI. He was at the Red Cross. Carl Byoir, who is one of the big names in public relations, was had a very senior job in the Committee on Public Information and there were others, and in fact there was a study done or a little survey done in 1970 by a public relations magazine, and they picked ten people who were pioneers. Now, this would have been 50 years after the CPI existed.

[0:21:00]

And half the people they mentioned were people who, who were pioneers were from the CPI and the others were all people who hadn’t even been alive when the, when the war went on. So in other words, those people were really memorable in the — in the next three or four generations of PR people who came, came along who were leaders. That, that was their prominence. Uh, and they’re, and they’re quite interesting, Carl Byoir being perhaps maybe the most interesting simply because he was both creative and engaged in activities that were questionable as far as ethical standards go, one of them being using front organizations that pretended to be grassroots, but were really run by the CPI.

Nick Hirshon: Wow. Well, and this speaks to the far-ranging impact, as you argue in the book, of the CPI, right, ranging from the public relations impact long term in government, propaganda, journalism. We’re gonna get into all of that. Let’s get into some of the work of the CPI itself. So it had some traditional –

[0:22:00]

forms of propaganda, as I think a lot of us might initially define it, a national newspaper named the Official Bulletin. It spread its messages through articles, cartoons, and advertisements in newspapers and magazines. But what I found especially interesting, and I’d love to hear your viewpoint on it, it had these unusual methods like reaching the American public through textbooks and Sunday church sermons and feature films and talks during intermissions. So what can you tell us about those tactics of the CPI?

John M. Hamilton: Yeah, so Creel … who rarely said a sentence that wasn’t an exaggeration, once said that the CPI used every method of communication at hand, and that is not an exaggeration. There was not a method they did not use. They used, even used Boy Scouts to hand things out or make it, to make little publications they’d give to traveling salesmen that they could hand out. It was, you know, they were, they were very creative, and they designed publications that are the size of your pocket so you could put it in your back pocket. I mean they were just, they were very, very good at that. And they had a very strong educational unit –

[0:23:00]

run by Guy Stanton Ford, who later went on to be the president of the University of Minnesota, and brought in, brought into the CPI the services of, of some of the leading scholars in the United States. Uh, many of them were historians, but they were also sociologists and economists and so forth, political scientists, and a lot of what they wrote was tendentious and scholarly questionable because they were so biased. And then the other organization you just mentioned was, was – and they had them for schoolkids, too, right? I mean they had, they had another division for, for K through 12. And then, and then they had an endeavor that, that is quite remarkable called the Four Minute Men, and these were people who got up in the middle of movies. In those days, films were changed, took several minutes to change the films, and the Four Minute Men, individual Four Minute Men in communities around the country –

[0:24:00]

would get up and give a speech. But what made this remarkable is it looked like a grassroots activity. Here you’ve got, you know, your local lawyer or your local mayor or your local important attorney or your head of a large real estate company who gets up, your neighbor, and gives a talk, and it’s, so it’s your neighbor talking to you, which, of course, has much more credibility. You know, we think, oh, what do journalists say about something, but you know a lot of times what people think is what they learned at Sunday School when the preacher says something, because that’s somebody you really know and trust. And so these local people got up and spoke, but they were very scripted from Washington. Uh, every week they had a different topic. The topic was decided in Washington. They were given speeches. They were told — or not a speech, topics, but outlines. You didn’t have to follow the outline or even give the speeches, the canned speeches they had, but you were expected to stay to the idea of the script and, and be very careful about what you said, not deviate, not go beyond four minutes. Uh, and they were monitored.

[0:25:00]

Uh, and so it looked like it was grassroots, but it was, as I say, managed from afar, and not to make too much of it but, you know, it kind of worked like Communist cells where you had these people all over, all over who are doing their work, but are, but don’t have a lot of freedom of activity. They’re, they’re, they’re all synchronized. And I mean I found, I just, for the fun of it, I got on a plane one weekend and went to Nashville, Tennessee. I wanted to see the Nashville, Tennessee file on the Four Minute Men. I thought that could be interesting. I mean it gives you some idea of how I did the research, too, just to get what – I wondered what, what about that?

Nick Hirshon: [Laughs]

John M. Hamilton: Well, it was a very productive trip. It was a very small file, but in it was a letter from the Committee on Public Information to the head of the CP to the Four Minute Men in Tennessee, and there would be a head in Tennessee and then various cities would have their own subheads, and they would have meetings with the Four Minute Men. And this was a script of how they were supposed to operate when they had, when the –

[0:26:00]

Four Minute Men heads met with their staff or their speakers. And it said something like 10:30 start the meeting, 10:34 say this, 10:48 say that. I mean it was scripted right down to the minute of what they were supposed to do in these meetings. Maybe they didn’t exactly follow that, but the point was they were, they were given lots of direction, and so it was a very effective technique. And at the end of the war, as astonishing as it may seem, there were 75,000 Four Minute Men. Now, some gave one speech, but many gave 200. So it was, you know, 200 is too big a number actually, but many gave a hundred. Probably a fairer number.

Nick Hirshon: Uh, well, I think that part of it is incredible because usually, at least my education of propaganda was more thinking of traditional vehicles like television, radio, newspapers but as you say, when you’re hearing it from trusted sources, your neighbors in the community, and just everywhere you go –

[0:27:00]

You’re going to a movie, you’re going to church, it’s a constantly around you. It’s a real new level of propaganda so I’m glad that you, you know, described that for us. Uh, we haven’t spoken yet too much about a critical component here, the news media. How was the press taking all of this? So the CPI, as you write, introduced a new dynamic into press-government relations, and reporters resented it, but they also depended on it because Wilson’s wartime programs were straining the resources of newspapers and magazines, and the press needed help keeping track of what the government was doing. So what were journalists’ attitudes towards propaganda and the CPI?

John M. Hamilton: Well, you, you’ve actually done a good job of summing it up. There had been press releases before. You mentioned it yourself that even McKinley had some and, and Teddy Roosevelt did an even more aggressive, was even more aggressive in terms of press releases. But under the CPI, press releases became really an aspect of government. They were, they were, they came out, whereas before there was a drip, drip, drip of press releases, now it’s a steady stream.

[0:28:00]

And the, the press would come to the press club or over the Committee on Public Information offices on Lafayette Square where they would pick up these press releases, and, and as we all know, people who cover the White House or other government agencies, they can’t afford to be too far away because something will happen and they need to be there to get the information because they don’t want their competitors to get it. Uh, so on the one hand they needed this help because the government had grown so vastly during the war, as I mentioned earlier, and, and many of the journalists who knew Creel liked him as a person, but not all that’s for sure, and even people who liked him would complain that he was too heavy-handed. So on the one hand, you had the need, the need for the government to give you information. On the other hand, you had Creel, who, you know, if he didn’t like a story you wrote, which was who cares, just a story, he’d be on the phone or writing you this very belligerent letter. And that made him a bigger target, and it, and it made, and it made enemies for him –

[0:29:00]

that he didn’t have to have because the press was so supportive of the war. This is the other part that’s so interesting. The press was very supportive. You know, we think of a turning point in press cynicism as being the end of the Cold War when it came out in Ramparts magazine and elsewhere that the CIA, for example, had people who were posing as journalists, or the CIA used journalists who were working journalists. And we, and, and we also know around that time that at the end of the Vietnam War we saw that, a lot of cynicism as a result of things that they were told. But there was an earlier turning point, and that was World War I where journalists believed a lot of things they said Wilson would do, that he ended up not doing. Uh, and at Versailles, for example, and things he sold out on that they felt he shouldn’t have sold out on. And also, they saw a rollback on a lot of the progressive legislation because big business was able to have a real resurgence as a result of the need to be mobilized and to be productive.

[0:30:00]

And so at the end of the war, people, some people who had been propagandists began to see, or had, had been supportive of propaganda, began to see that it set in motion an antidemocratic process that made them more cynical about government. And I think what we’ve seen since is not one, only one event that has done to, done that, but an accumulation of events over time where you have a paradox that it was just the government uses propaganda in order to get what it wants on a given day, but it also undermines credibility of the government because people later on come to see what it really was. And we look at the Vietnam War that, obviously a very good example of that, or the Iraq War, because wars usually have such dramatic consequences. The line is more palpable and has greater repercussions.

Nick Hirshon: Sure, and when you were talking about Woodrow Wilson before, you were mentioning the comparison to Barack Obama and Donald Trump in the sense that as they campaigned using social media, they then made social media a big part of their presidencies.

[0:31:00]

This kind of natural carryover, and that happened with Wilson campaigning in 1916 and then starting the CPI in 1917. I wanna kind of get into that, into contemporary politicians and what you think here. Since World War I, you write that government propaganda has expanded relentlessly, coming in a daily flow of press releases, Facebook and Instagram posts, YouTube videos, livestream speeches, and scripted press conferences, and I’m sure we could talk endlessly about propaganda in contemporary American politics, but how have you seen the legacy of the CPI manifesting in recent years in the presidencies of Donald Trump and Joe Biden?

John M. Hamilton: Every president has some transgression when it comes to overuse or abuse of its, of the chief executive’s information power. Uh, Trump, I mean, I never expected we’d have Trump when I started doing the research on this book. Trump makes my book seem more relevant because he’s so dramatic. I mean there’s, there’s nothing he would leave untouched to –

[0:32:00]

propagandist — propagandize himself, including, you know, putting his name on coronavirus checks, or when he’s coming out to dispute the election having “Hail to the Chief” play in the background. I mean he has all, the president has all of these tools to aggrandize themselves and, and establish the fact, whatever truth they want to establish. The problem here is one that – and this is always difficult when you write about something like this. The problem is that to understand what’s happening and to figure out how to deal with it, you have to — you have to deal with a lot of subtlety. Uh, and in fact it’s difficult to think of a problem that’s more difficult to unravel than this one, so I’m gonna take a moment to try to explain it because one of the reasons I wanted to write this book was to show the difficulties of dealing with propaganda in a democracy. So that, one of the great things –

[0:33:00]

about our American government is that it is such a trove of information. We can find out information on all kinds of things, not just the weather reports and trade statistics, but if you — if you’re really interested in fishing, fishing on a river, you know, at some place in the United States, somebody has taken the temperature of that water. And there’s all kinds of reports that are put out. It’s just — it’s mindboggling. I never really use that word much, but in this case it is. It’s the – we — our government turns out vast quantities of information. Some of it’s basic stuff like traffic statistics, traffic accidents in a given year, but also some of it’s more complex, dealing with scientific studies and dealing with health and, as we now know from the coronavirus pandemic. That’s a very important thing in a democracy. You know, Alexander Hamilton, one of the first things he did when he became Treasury of the Secretary is he started figuring out how many ships came into port, and he was measuring what products came in, and that became –

[0:34:00]

a very important source of information for business people. And, and his bureaucracy, by the way, was by far the largest in the federal government because economics is a place where you want to get data. So that’s good. The second place, the second thing that deals with government, second aspect of this, is that you want your presidents to actually argue for their point of view. You have, you have an agenda. You want to argue for it. You want to provide the best case you can make for it. That could be called, in a sense, propaganda. You’re — you are as the elected official saying, “I think we should raise the minimum wage. That’s what I think we should do, and here are the reasons why I think we should do it.” And you and your officials who are appointed are entitled to go do that, to make that case. But here’s where it gets to be complicated. The Labor Department starts putting out data that doesn’t just tell you about wages, doesn’t tell you what the varying wages are or the statistics on wages, but starts saying things like you need to go lobby your congressman or woman –

[0:35:00]

to vote for raising the minimum wage. So effectively we’re using the government information apparatus, which has grown exponentially, to tell taxpayers, use taxpayers’ money to tell them what to think, and there’s something wrong with that. The problem is how do you fence this back? In other words, how do you draw the line? Right now, for example, just to give you one law, you’re not allowed to use the government, to use the government, to use government information equipment, apparatus, you’re not allowed to use that to give a speech that’s purely political on, you know, on, on minimum wage, but if you have just a few pieces of statistics in there that are fact based, then how do you decide what shouldn’t be in and what should be in? You’d never get prosecuted for that. You never get your, even though you’re, you’re not supposed to do it, the question is how do you divide it up? So also another problem that the people who would have to enforce this ultimately are who?

[0:36:00]

The Justice Department. Well, the Justice Department reports to the White House. So to just get right to the point, we don’t know how much information the government puts out. We’ve stopped even trying to count. There’s no way to do it, or there hasn’t been anybody who’s tried to do it. That’s number one. And what we really need to know is we need to have a kind of census so we can figure out how, what’s the government doing. Used to be we had, you know, you could just look at how many public affairs offices you have, but now all kinds of people are putting out information. They don’t have that title at all. If you go to the policy and planning staff of the State Department, all of those people are tweeting. Huh. You know? So they’re propagandists. So how do you decide who they are? So we need to know better about what the government’s doing, and then we need to do a better job of having some rules of the road of what’s okay and what’s not, and maybe we need an outside group to help monitor this. We certainly need better laws, but we also need something else, and this is a sad, and sadly absent right now from our government, and that other thing we need is we need statespeople who –

[0:37:00]

look at principle as opposed to merely promoting their own point of view. So, to use an example, when a president abuses their propaganda power as, say, Obama probably did in selling the Iraq deal because he did some things that were controversial on social media, the Republicans get very upset, but then when the Republicans do something and it’s their president, the Democrats get upset, but nobody gets upset over the principle of it, and this, and this is a problem. So Republicans get upset when, when the Obama administration goes after Fox News, and then we get upset, you know, when the Trump administration goes after the New York Times. Somewhere along the line we need to look at the democratic, we need to respect the democratic process for what it is, not that we get the outcome we want but that we respect and privilege the process, because in the end government will have more credibility and that’s, and that’s what propaganda erodes.

[0:38:00]

Nick Hirshon: Well, as we wrap up today’s episode, I’d like to end with a question that we ask all of our guests on this podcast. We’re titled Journalism History. Why does journalism history matter?

John M. Hamilton: So there’s a question that does history matter, and if we have to make a case for that we probably won’t be able to because either you understand why history matters or not. Uh, it’s not true that past is prologue. That’s bullshit because, you know, history doesn’t always play out exactly the same way, but you do learn some principles and you do understand how your society evolves as a result of history, and it gives you greater perspective on why what happens today. Uh, journalism history matters for the same reason, only it’s about journalism. We need to know how people know. In fact, I always talk – our school is very good at media and politics, and I — the Manship School of Mass Communication at LSU — and I always argue that we’re not interested in journalism and we’re not interested in politics. We’re interested in what people know and how they know it.

[0:39:00]

And how do we improve what they know? That’s the goal. And I think the Committee on Public Information story is one that helps us think about the obligations to live up to that and what could get in the way of it, and maybe help us think about what we can do to fix it.

Nick Hirshon: Well said. Well, thank you again, Jack, for joining us. The book, again, is Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda. The author is John Maxwell Hamilton. Jack, thank you for being here on the Journalism History podcast.

John M. Hamilton: Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate it.

Nick Hirshon: Thanks for tuning in, and additional thanks to our sponsor, Taylor & Francis. Be sure to subscribe to our podcast. You can also follow us on twitter @JHistoryJournal. Until next time, I’m your host, Nick Hirshon, signing off with the words of Edward R. Murrow. Good night, and good luck.

1 Comment