For the 76th episode of the Journalism History podcast, hosted by Teri Finneman, Tim Ziaukas focuses on the crisis communication history of Titanic while historian Ron Rodgers discusses his research, “The Titanic, the Times, Checkbook Journalism, and the Inquiry into the Public’s Right to Know.”

For the 76th episode of the Journalism History podcast, hosted by Teri Finneman, Tim Ziaukas focuses on the crisis communication history of Titanic while historian Ron Rodgers discusses his research, “The Titanic, the Times, Checkbook Journalism, and the Inquiry into the Public’s Right to Know.”

Tim Ziaukas is professor emeritus of public relations at the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford. Ron Rodgers is an associate professor of journalism at the University of Florida.

Transcript

Tim Ziaukas: Some informal studies have suggested that Titanic, Jesus Christ and the American Civil War were the three most written about subjects of the 20th century.

Teri Finneman: Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to reexamine the stories you thought you knew, and the ones you were never told.

I’m Teri Finneman and I research media coverage of women in politics.

Nick Hirshon: And I’m Nick Hirshon, and I research the history of New York sports media.

Ken Ward: And I’m Ken Ward, and I research the journalism history of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Teri Finneman: And together we are professional media historians guiding you through our own drafts of history. This episode is sponsored by ship historian Tim Yoder. Transcripts of the show are available at journalism-history.org/podcast.

The Titanic. it’s one of the most famous events in history, and a story that people –

[0:01:00]

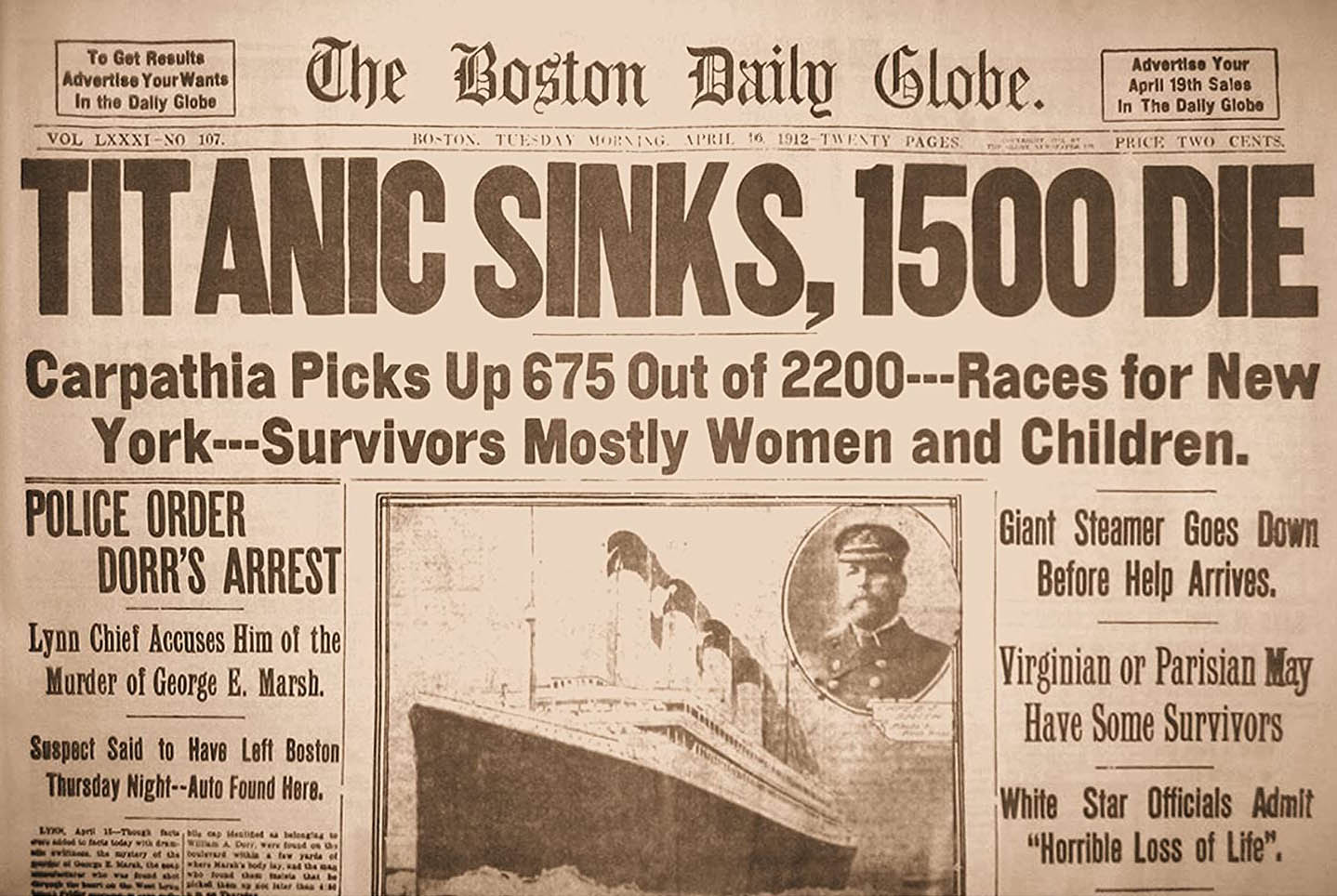

think they know. On April 15, 1912, the ship that claimed to be unsinkable became one of the world’s most famous tragedies after hitting an iceberg. The blockbuster movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet was the first film to reach $1 billion, illuminating the continuing public fascination with the crisis nearly a century later. But there’s so much more to the story.

Our episode today explores what happened before and after the sailing and sinking of the ship, and how Titanic became a pivotal moment in public relations in journalism history. Our first guest is Tim Ziaukas of the University of Pittsburgh who will discuss his research “Titanic and Public Relations; A Case Study.”

We then visit with Ron Rodgers at the University of Florida to discuss his study, “The Strange Absence of News; The Titanic, The Times, Checkbook –

[0:02:00]

Journalism and the Inquiry into the Public’s Right to Know.”

Tim, welcome to the show. So we’re talking about Titanic today and your research on it. And in your study, you note, “Despite the fact that the sinking of the luxury liner on April 15, 1912, is the most examined events of the 20th century, the disaster’s place in the history and evolution of public relations has gone largely undocumented.” So why do you think it’s important to study the public relations aspect of Titanic?

Tim Ziaukas: Ah, thank you. Well, Titanic is positioned in a – in a really vital spot in the history of public relations. Looking before Titanic, you have really the rise of big business. These companies like Standard Oil, or the railroads, that really had the communication needs of small nations, or maybe even large nations.

Then, in relation to that, you had –

[0:03:00]

the muckrakers who were throwing barbs and demanding progressive reforms. You have the rise of, of a new and different kind of media along with an illiterate class. And then right before World War I, where notions of propaganda, and to use Edward Bernays’ term, impropaganda, kick in.

Right before that, you have massive consumer product and service that has multiple internal and external publics. Many different kinds of messages that need to be articulated to various publics. And then of course it’s, it’s a disaster.

So it not only becomes a piece of sort of business public relations, but when the Titanic sank, a metaphorical Titanic rose up and still lives with us as an image-making machine. So it’s a –

[0:04:00]

complicated phenomenon. You had said that, you know, that I had said that it was among, and it is among, the most discussed phenomenons of the 20th century. Some informal studies have suggested that Titanic, Jesus Christ and the American Civil War were the three most written about subjects of the 20th century. Um, yeah.

So I think – I think that’s why, you know, it is – it’s a big part of the 20th century. It’s an image-making phenomenon that is still making images – for us, and, and it’s there as a business example of so many things.

Teri Finneman: So let’s talk about the White Star Line in particular, which was the corporate owner of the ship. You write that Titanic itself was conceived as a public relations device. So give us some of the context about why it was needed as a public relations device for this company.

Tim Ziaukas: Okay. Ah, well the American entrepreneur JP –

[0:05:00]

Morgan had acquired White Star Line in 1902. Within a few years, it was clear that that market was tightening. It’s — White Star’s rival, Cunard, had these faster ships: the Lusitania, the Mauretania, and, and White Star was being eclipsed.

So J. Bruce [Ismay] is named White Star’s managing director, got together with the bigwigs and decided to reposition and rebrand White Star and create a line of ships that would not use speed as its brand, but its scale and sumptuousness, and that it would be the most elegant passage, you know, possible.

So, you know, and, and even their names, the names were derived from classical mythology. This was going to be the wonder of the age, demigods. White Star was never good at –

[0:06:00]

or never cared really about the sort of primitive public relations that Cunard even did, but they changed their mind for these – this special class of ships.

Ah, you know, for now, like when Titanic was launched before it was fitted out, this huge celebration, this huge party, JP Morgan showed up, deck plans were printed out, big posters, postcards, much more what we would call publicity in public relations than ever happened – than ever happened before even in New York.

And the White Star Line, they hired their first publicity person David Lindsey, who would have a special job, you know, eventually, when Titanic didn’t arrive in New York. So the whole idea of this was to rebrand,

[0:07:00]

reposition and get publicity for White Star Line in the face of Cunard who was doing better than JP Morgan’s White Star.

Teri Finneman: The basic facts of Titanic are widely known. At 11:40 p.m. April 14, the ship struck an iceberg. The first distress call went out at 12:15 a.m. At 2:20 a.m., the ship broke in two. And it was 4:10 a.m. before the Carpathia arrived to help survivors. Overall, 706 people survived and 1,517 people died, but what most people don’t know is what was happening elsewhere.

So first off, tell us about 21-year-old David Sarnoff and the unusual story of his breaking the Titanic news from a New York department store.

Tim Ziaukas: Okay, this is another interesting piece of public relations. The Wanamaker Department Store had installed

[0:08:00]

a commercial wireless, a commercial radio station atop its stores in New York and Philadelphia. It was a PR device. It was look at how interesting this is. We can talk to people around the world with Morse code and, ah, was – it was a fun thing.

Twenty-one-year-old David Sarnoff, who would go on to have a legendary career in broadcasting, happens to be working. Now he turns this, as others do as well, into, you know, this hagiography of – because he became such a big deal. So we get this story of, “And for three days and three nights Sarnoff labored at the, you know, at the – at his wireless.

And well, I’m sure he did, but his actual connection to the complicated crisis communication that goes on I don’t think has ever been completely or satisfactorily articulated, and yet – I mean he’s clearly a big deal and clearly involved. He hears this

[0:09:00]

over the wires.

He, you know, he’s 21 years old, Titanic is 1,400 miles away, and he hears SS Titanic ran into iceberg, sinking fast. Sarnoff alerts the media. Now keep in mind that the wireless operators on Titanic, Bride and Phillips, and, and the guy on the Carpathia and Sarnoff, they all worked for the Marconi Company. They don’t work for the ship.

It – all of that, that is so primitive at the time. Nobody knows what’s really what, what this means. In fact, in the org chart of the Titanic, the wireless operators are in with the pastry chiefs. And the, you know, they’re not – it’s not – it’s not – and they’re taking all kind of what we would consider inconsequential messages. It’s people saying, “I’ll meet you on the pier,” or, “What’s happening with you?” I mean it was just social things.

[0:10:00]

Um, Sarnoff, though, begins to tell the world what’s going on, and he takes control of the story in a way that the White Star never did. I mean, talk about the origins of crisis communications. It’s not even the origins. It’s way back – we have to get to the origins.

Unbelievably White Star didn’t have its own wireless, so they’re getting information presumably from Sarnoff as well, but to get the – they’re getting it from the media when they can, but they have to wait until other ships like the Olympic, which had the most powerful wireless at the time on the sea,

when the Olympic people would, would hear something, they would send a telegram to Montreal. Montreal would then call a Western Union station and into New York, and then a guy on a bicycle would take it down to the White Star’s office –

[0:11:00]

I mean it was ridiculous.

So the Marconi employees suddenly are controlling really completely the story right then, and Sarnoff’s at, at the – at the head of it. And that’s the way it was. That wasn’t – that’s the primitive nature of what’s going on at the time. It isn’t like White Star screwed that up. Um, no one knew any better.

Teri Finneman: Wow, that was fascinating. Ah, yeah, let’s keep – let’s keep delving into this. So we have this brewing major communication crisis, and Phillip AS Franklin is in charge of the New York office for the White Star Line, and ended up essentially as head of public relations for one of the worst disasters in history.

Ah, one of his first blunders was trying to talk the Associated Press out of running a story. Tell us more about how he tried to control the public relations of this disaster.

[0:12:00]

Tim Ziaukas: Well, I think I’m in a – I’m in a small – I’m in a small boat. I feel sorry for Franklin. Some people believe, including I remember I talked to Charles Haas, who’s one of the – who was one of the world’s leading experts on Titanic, and he thinks that Franklin was just lying and, you know, just, you know.

I don’t – I don’t really think so. You know, to say that they were unprepared isn’t even fair. It isn’t like they could have prepared. It’s like asking us now – well we are kind of – I think we, we as a culture are probably more prepared for aliens landing, and what would we do and how would we do it because of what begins with the Titanic, and then moves through the 20th century as crisis communication theory evolves. It was nothing then.

So there’s Franklin. He’s awoken in the middle of the night by the AP, and he says, “I don’t know what’s going on. Can you hold this story?” They said, “It’s already gone out. What’s happening?” and then begins this mad –

[0:13:00]

chaos.

I mean JP Morgan is in Europe so he’s no good. Not that he – not that the CEO would be involved in this at this point anyway. Ah, J. Bruce Ismay is on the Carpathia, you know, and another – I mean he’s the evil guy who – say who had the audacity to live, and he did and he’s a mess. He’s in the captain’s cabin on the Carpathia experiencing I think a nervous breakdown.

Um, so who’s in charge? All this stuff that we know about crisis communication really comes decades later. I mean if you look at it, I mean I think it’s – a lot of people may argue with me. I think modern crisis communications really exists with things in the ‘80s.

It’s Three Mile Island, it’s Tylenol, it’s the Pepsi syringe thing, it’s all of that stuff and people say, “Wow, you know you need to have a single –

[0:14:00]

spokesman. You need to have an articulated plan ahead of time. You need to identify a team. You need to, you know, only have one person.” All that stuff is decades later.

So Franklin is trying to get all kind of information. He’s out of his mind. Um, the whole – the heartbreaking thing with the train. Did he actually contact the relatives of the passengers and say everybody is fine and we’ve rented a train, or we’ve chartered a train, we’re going to take you so you can meet them when he knew they were dead?

I mean I can’t believe that, and maybe that makes me naive. But I think that he actually did put a couple of messages together that were garbled at the time. And could we even imagine the panic all these people are under? It’s unimaginable. If we had time, we could read some of his statements, but, you know, I believe him. I believe he was telling the truth.

And again, I’m probably in a small –

[0:15:00]

boat there. I don’t think he actually lied, but he was heartbroken. And he’s the one who says that we thought it was unsinkable. Um, all the other collateral material that came before that I have found, and I looked, said it was practically unsinkable. There was always that out. There was always that. It’s Franklin who, during the press availability sessions, says, “I thought it was unsinkable,” and, and something begins there.

So it’s, it’s complicated and I feel sorry for Franklin.

Teri Finneman: Yeah, do you have a couple of his statements available?

Tim Ziaukas: Okay, yes. Okay, here, here he is – okay, they’re asking him what’s going on and he says, “We have heard nothing directly from Captain Smith himself.” The captain who is clearly dead by now. “We are not sending any orders from here. He has his hands full –

[0:16:00]

without being bothered with orders. We contribute the failure to hear from him to the fact that the wireless apparatus is disabled. We place absolute confidence in the – in the Titanic. We believe the boat is unsinkable. And although she may have been struck at the bow we have – and had settled to the water, we know that she would remain on the surface,” and on and on.

Um, when it’s clear that, that so many people are dead and, and, and the ship is in the bottom of the – of the ocean, when he got the telegram, he says, “It’s horrible.” Immediately after the telegram was received by Franklin, he goes out and, and tells the media that the ship has sunk, and they don’t even listen to his statement. Everybody runs out.

By the end of the day, Franklin is weeping in public and he said, “I thought her unsinkable and I based my opinion on the best expert advice.

[0:17:00]

I don’t understand it.” I believe him.

Teri Finneman: Wow. So we have now the Titanic survivors finally arriving in New York, so what did Franklin do once they arrived?

Tim Ziaukas: This is – this is the most interesting thing to me. Franklin immediately boards – well, meanwhile, Ismay is sending telegrams to Franklin and in code with his name spelled, his last name spelled backwards. So we, you know, this didn’t take much to figure out.

But he immediately boards the Carpathia and there was a two-hour meeting with Ismay and Franklin and the ship doctor because I think Ismay was on the verge of going over the edge, and who could blame him. Ah, there’s no record as to what was going on in that meeting. If there’s anything about the Titanic I would like to know, it’s I would love to have a recording of that meeting.

[0:18:00]

Then the passengers start to come off and, and they start telling their story. Actually, they send out a declaration of Titanic independence kind of that’s, that’s actually sort of interesting. And I mean everybody starts telling the story, and I have a quick personal thing I’d like to add when I get done here.

But when – before they get off they issue – they realize that, “Wow we are -” I don’t think they are – I don’t think they would have articulated this wholly, but they certainly felt that the world that they were going to land in was now different than the world they left in South Hampton.

And they write, “We the undersigned surviving passengers from this steamship Titanic in order to forestall any sensational or exaggerated statements deem it as our duty to give the press a statement of facts which have come to our knowledge and which we believe to be true.”

[0:19:00]

And they begin to sort of tell their story in a way – and then they fan out and begin telling them really for the next 80 years. It’s — it’s a remarkable thing.

And everyone becomes a new kind of celebrity. It’s for the rest of their lives anyone who had anything to do with the Titanic suddenly if you were there it – this isn’t like it’s like the precious items from Tutankhamun’s tomb. This is like a fork from the Titanic is now imbibed with myth and is like, “Oh, it’s a fork.” It’s like, “Okay.”

It is something different. The alchemy of, of publicity is sort of changing the nature of things. I was at a conference in 2000 on the mythology of the Titanic at South Hampton, so it was 20 – 21 years ago. Um, 21 years ago –

[0:20:00]

this summer. And I happily got to speak to the last surviving person at – on the Titanic, Millvina Dean. Charming lady. She was a baby, but for the rest of her life, she’s just telling her story from what she heard from her mother. She was a very small child.

And, and at this – at the cocktail party before the formal academic conference where I talked about this stuff, public relations and Titanic, a flurry hit the room and in walked a guy and someone said to me – he was an old man. And someone said to me without a hint of irony, “Oh, it’s the fetus.” I said, “What?” And, and they said, “He was a fetus on the Titanic.”

Teri Finneman: Oh wow.

Tim Ziaukas: No one thought this was weird, or funny, or odd, or ironic, or too much. And one of my regrets is I was so astonished that this guy had –

[0:21:00]

achieved his lifelong fame before he was actually born by being a baby in his mother’s womb, a fetus in his mother’s womb at the time. I was so astonished I continued talking to Millvina Dean and alas, missed my opportunity to speak to the fetus.

Teri Finneman: Wow.

Tim Ziaukas: Um, which I – which I regret. But that’s the extent to which this event has its, its image-making potential. It’s still going on: movies, Broadway shows, everything. Um, still fighting now. Speaking of the – what are they? The wireless people.

Ah, the wireless – the last I heard the wireless is still hanging and there’s argument we – should we go in and get it. We – you know, we could send in a robot and bring out the wireless equipment, but for some people it’s still a grave,

[0:22:00]

um, and the complications around that.

So we – the Titanic, as a metaphor, ah, will always be with us. It will not go away. It will not, dare I say, sink. From ship of state to is it a – is it a parable about feminism, votes for women but boats for women. Should, should, should they have gotten in, in first since they wanted the vote? It’s a class story. It’s a – it’s a prelude to the war. It’s a technological warning. Um, we have – the next war will clearly be fought digitally. That is the Titanic metaphor as well. We see it everywhere.

So, as an image making, as a PR device both from business and then as a cultural, PR element, it’s hard to beat. It’s a good one.

Teri Finneman: Yeah,

[0:23:00]

So what do you think are the overall lessons for public relations in crisis communication that can be taken away from Titanic?

Tim Ziaukas: Well I – as I said, I think they are acting in a world in which there is no theory yet. It was unimaginable that this would happen on such a scale, and so publicly. So, I mean, the lessons are we’ve got Titanic, we’ve got the war, but really modern crisis communications doesn’t evolve much until — with its legal and ethical guardrails I think until the 1980s because they did everything wrong.

And not that it was even wrong. There was no context, no theory in which to judge what they were doing. Um, so I mean, again, maybe I’m being naive here. I don’t blame them. Ah, you know, was Ismay ridiculous at times? Yes.

[0:24:00]

Um, well was Franklin naïve? Of course. Ah, where was JP Morgan? They had no plan. They had no idea that, that anything like this could happen. They didn’t even have the wireless. So we have Marconi employees telling their story, coordinating nearly everything out of their control. And, and, and people acting with, without a plan, without something to look at while the adrenalin was squirting out of your ears.

Um, people are going to act – I don’t think they act as evil. Um, they act because they’re fighting. So you have Ismay telegraphing Franklin and saying, “Hey, get the Cedric – get one of these ships. We want to go immediately back to, to England.” Because he was afraid.

Does that mean he was evil and didn’t want to – he didn’t think there was going to be a commission immediately, which there was. He didn’t think there was going to be a hearing right away –

[0:25:00]

and there was. He was scared and he wanted to go home. They immediately quit paying the crew that survived. Again, that went horrible. Everybody is in New York with no hotel money, with no money for food and you, you quit paying them?

So I mean the – nobody had a plan. Nobody could look and say, “Oh, I’m scared. I don’t know what I’m doing. But oh, I’ve got a crisis plan here. I’m going to call a team. Oh, I’m going to have one person talk to the media. Oh, I’m going to do this, this, this.” I mean none of that was there. So and that wouldn’t be there for quite – for decades following the Titanic.

So, you know, the lessons are, okay, let’s start there and see what they did and then build up. Let’s get to Three Mile Island and see what happens. Let’s get to, you know, some of the disasters in the ‘80s. Let’s get to the Exxon Valdez. And, and, and then now we’re, we’re beginning to develop theory and we –

[0:26:00]

kind of know what to do in the shadow of those catastrophes.

Teri Finneman: Well, this has been absolutely wonderful. This has just been fascinating, so thank you so much for joining us today.

Tim Ziaukas: Well, thank you for asking.

Teri Finneman: So we just got done talking about the immediate aftermath of the Titanic from a public relations perspective. We’re now going to examine the journalism perspective. We’re now joined by Ron Rodgers to discuss his article “A Strange Absence of News: The Titanic, the Times, Checkbook Journalism and the Inquiry into the Public’s Right to Know.”

So we’re focusing today on the story of Harold Bride who was the surviving Titanic wireless operator. Tell us more on who he was and why he in particular became such a newsworthy figure.

Ron Rodgers: Well, he was – he was 22 years old. He was a junior wireless officer aboard the Titanic. He worked –

[0:27:00]

with a senior telegrapher Jack Phillips. He joined the Marconi Company only in just July of the previous year, and, you know, two things happened with him. He becomes a protagonist. The story he told to the New York Times, you find it cited in works over the last century, but he was also kind of cited as a hero because of his work on the Titanic, and then later his work.

Well, he was injured on the Carpathia, the rescue ship, so he was a protagonist and a hero, and part of that story was that he and Jack Phillips stayed, stayed in the telegraph office until the very end and then went overboard. And him and Phillips,

[0:28:00]

along – and 20 other survivors were clinging to an overturned boat and their bodies were half in the water. And after they were rescued, Phillips died, and Bride was injured. He sprained – a severe sprained ankle on one leg – one foot, and frostbite on the other.

And when he got aboard the Carpathia and he recovered a bit, he went into the telegraph office and, and helped out Harold Cottam, who is the Carpathia’s telegrapher, to start sending messages back to the United States. Oh, actually both, both ways, with messages from the survivors, which is what they were ordered to do. And they had a stack of 600 to 700 messages they, they had to send over the wireless.

And, in fact, even after the ship had pulled into the dock in New York City, the reporter had to hunt him down and find him –

[0:29:00]

because he was still in the office sending messages from the port to survivor’s families and friends.

Ah, and so he became the center focus of all of – all of those hearings dealing with the journalism part of, of the story. And in fact, he was – when he – when he went into the hearing room to testify, he had to be carried in with, with his two feet bandaged and, and then set in a chair. He couldn’t stand up.

Teri Finneman: Yeah, and we’re definitely going to come back to those hearings in a minute.

Ron Rodgers: Yes.

Teri Finneman: Let’s talk a little bit about, you know, being on the ship with no concrete news from the ship coming immediately and Titanic survivors still en route to New York now on the Carpathia. You wrote about crowds of people forming outside the White Star Line office in New York, begging for news and getting none. And as a result, conspiracy theories started to form with one rumor that JP Morgan didn’t want any news out –

[0:30:00]

until after the stock market had closed.

And ironically, the New York Times, who we’re going to get into more here, ran a headline that stated, “Four days of terrible suspense breed wild rumors.” And at the exact same time, accusations arose that Bride and the Carpathia wireless operator were purposely holding back news so they could cash in by selling their stories.

So we – before we get into that specific incident, give us a little context of how common was checkbook journalism at this time.

Ron Rodgers: Well, you know, this is one of the things that intrigues me about this, this story. Because in the early 20th century, late 19th century, it was an accepted practice. You could find this cited in journalism textbooks of the time. And in fact, Frederic Hudson, the former manager of the New York Herald, said it was a common practice –

[0:31:00]

among journalists to pay for stories.

And, and, and then when – then when I see this and then I think about the era we live in now, I sort of wonder how, how things changed from then to now, right? How did – how did this ethos about it is wrong for journalists to pay for stories, where does that all come from and whatnot? That’s something that would be difficult to explore, I think.

Ah, but I – but I would say that the hearings and the discussion and the controversy and the – and the many stories about this issue that appeared in the early 20th century is sort of the start of a reconsideration of all this. Ah, but it – well one thing interesting about this whole – this whole issue about checkbook journalism in relation to Marconi and the New York Times is that in 1909 a man – a telegrapher, a wireless –

[0:32:00]

operator named Jack Binns became internationally famous.

He was on the White Star Liner Republic, which crashed into a cargo ship down, I think it was down by Florida [Nantucket], and his messages across the wireless saved hundreds of lives. Ah, and, and when he got back to the States, he sold his story to the New York Times, which made him even more famous.

And one of the things he said in public was that he sold it to the New York Times because he got a message from the Marconi Company to “Reserve the story” for the New York Times because of Marconi and his company’s friendly connection with the New York Times.

Ah, and so there, there’s, there is just an example that –

[0:33:00]

that reveals that it was a fairly common practice and, and, and it also was a harbinger of what happened three years later.

Teri Finneman: Yeah, so let’s talk about that. So did the wireless operators indeed sell their Titanic stories to the New York Times, and if so, tell us the story about how that was arranged.

Ron Rodgers: Well, yes, they did. And how it was arranged was of course the controversy. And I don’t think – even in all the research I did into this I don’t – I don’t know whether we, we know for sure, right? It — it’s so confusing with a lot of – a lot of allegations published this fact back then and charging Marconi with, with, restricting his telegraphers from giving away the news and whatnot.

I think what we can say is that yes, Marconi arranged to allow them to sell –

[0:34:00]

their stories if they wanted to, okay? One of the questions was, okay, so they’re out at sea, and why are they not sending stories about the disaster and how the wreck happened, and how it sank and whatnot like that.

And the, the excuse was, and I think it’s a legitimate excuse, they had all these survivors on board the Carpathia and they – and they handed – they handed out wireless forms for them to fill out messages to send to their families back home. And so they had a stack of six or seven hundred of these messages in the office and they were busy sending all of those message.

And more than – and more than one time, both Harold Bride and, and Harold Cottam when they testified and when they talked about it would say that they had too much work to do to, to,

[0:35:00]

to send messages about the wreck, you know, what, what all happened. They were – they were notifying people that these people survived and whatnot.

The other thing is, and this is – this shows up in the testimony later by Marconi and, and in editorials and stories by the New York Times, it said that Marconi wireless operators were, one, not allowed to act as reporters. They were this – they were told that that was – that was company policy. The other thing is the British law at the time did not allow them to pass on news. That’s not – that was not their function and they were not allowed to do that, okay?

So the other question was then, then, how did this – how did anything get communicated to them about the fact that Marconi was trying to set this up for the –

[0:36:00]

New York Times? And the allegations were that the messages were going back and forth while the ship was at sea. And Marconi and others testified for the company and, and the New York Times also says that they did not send that message until the Carpathia was approaching New York City and about ready to dock.

So, ah, that was – and that was a dispute that was going on. It shows up in the hearings in Congress, but it also shows up in the news at the time. People complaining that this story is being held back and the New York Times is trying to reserve it for themselves.

And so that’s – that – you know, that’s a question that’s never, as far as I can tell, has never definitively been answered. I suppose one could go, if possible, into the archives of the Marconi Company and, and also to

[0:37:00]

to the New York Times, if you could get into them, and actually explore the messages that went back and forth and maybe you could discern that, but, but that’s still something that’s left in a kind of fog of mystery.

Teri Finneman: Yeah, so let’s go back to what you were talking about earlier with this inquiry. Ah, with so much chaos and, and the uproar over holding back public information for checkbook journalism, Republican Senator William Alden Smith of Michigan quickly became chairman of the committee to investigate the Titanic disaster.

An interesting fact to mention for our Journalism History listeners here is that Smith himself was a newspaperman, the owner of the Grand Rapids Herald. He was so bent on getting the truth out of what happened that he was one of the first ones to board the Carpathia when it docked in New York. And by, by April 19, just four days after the Titanic sank, the Senate inquiry –

[0:38:00]

began. Even Marconi himself with the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company was made to testify.

So is there anything else interesting about Marconi’s testimony that you wanted to let us know?

Ron Rodgers: It started just four days after the – as the story goes from some, some witnesses, that Smith heard about this and he actually wrote, wrote down the request to create this committee on the back of an envelope and handed it in and they approved it.

Now one of the reasons that he went to New York was, which would make an exciting movie, he had heard that some of the White Star officials that had survived and were on board, and, and other survivors of the crew and whatnot were, were getting ready to leave and go back to Britain.

And so he –

[0:39:00]

sort of rushed up there with his committee and, and corralled them before they could leave and forced them to testify here in the States. I think the report would have been quite different if it – if it – if he hadn’t done that. They actually took out a — they took over some of — I think it was the Waldorf Astoria or someplace. A big room in that hotel and, and, and held a meeting for a few days before they moved it all back down to D.C.

So, and, and during that inquiry, they talked to 82 survivors and marine experts and, and finally issued a 1,100-page report. Now, the thing, before I talk about Marconi for a second, is we should note, too, that the focus of the hearing was the cause of this – of the disaster, and, and, and that the Times reporting and how they reported that story and whether –

[0:40:00]

they did anything too nefarious to gather that information was sort of a footnote of the story.

But it became a bigger issue because papers were publishing it all over the place, especially in New York and on the East Coast. And so, it becomes a bigger story than it really was in the confines of, of the hearing. Though Alden Smith kept pounding away at it to the point that some of his – some of the committee members were about ready to revolt over it because it – you’re just basically going off on inconsequential stuff, and we need to focus on, on the actual charge for finding the – finding the cause of the crash.

In the testimony that he gave, Marconi denied knowing anything about holding back messages. He talked about the fact that what, what they did sell was their personal experiences and nothing about the wreck.

[0:41:00]

And so essentially that same defense over and over again.

I think one of the issues about the whole hearing that, that I find intriguing and why I looked into it and wrote the paper was that it deals with these, these early formations of, of a news ethic, of social responsibility, of the – of the press and, and the public interest. All of this is coalescing here. This is kind of a critical junction in the early 20th century.

Keep in mind they’re – at the time, there was no nationwide code of ethics for the professional journalism. None at all. They were – they were state ones and local ones but there was no – there was no nationwide one. Not until 1923 when the ASNE enacted the Canons of Journalism. And the heart of the Canons of Journalism is about social responsibility and the need to –

[0:42:00]

serve the public interest and not the private interest. And we hear all of this going on within, within the hearings dealing with Marconi and the New York Times.

Teri Finneman: Ironically on April 19, the day the inquiry started, the New York Times ran Bride’s firsthand account, ah, which is still easily findable in historical archives, and it’s a really fascinating piece of writing. But what’s relevant to our discussion today is this insistence in the original piece that, as you said, he needed to send out those personal telegram messages to survivors rather than send out news to the public.

So let’s talk about the New York Times itself, which was being accused of suppressing public interest news for profit. How did the New York Times respond to this?

Ron Rodgers: So essentially Smith is saying the disaster information, and this is a quote from him, belongs to the public, and it is its right to have it without delay, okay?

[0:43:00]

So you hear those whole ideas about the public interest informing that assertion. The information belongs to the public and its – and it has a right to have it without delay, okay? And that was the corner of it.

But if you stand back and look at the whole story, it seems like that’s fine to say that, but if you believe Bride, and Cottam, and Marconi and, and the New York Times, they weren’t – they weren’t allowed to send out that information even if they had it, and they made no deals to do so.

So anyway, it’s so — anyway. But in defense, and this is something New York Times insisted on also, they never – they insisted, both in their editorials and the stories and, and in – and testimony, they never asked to reserve the story until the ship –

[0:44:00]

was about to dock. And again, they pointed the fact that Marconi forbid telegraphers from reporting news, and they also pointed to the fact what Marconi noted was that British law made it illegal for them to do so anyway, and that they sold accounts of their experiences not the story of the wreck, okay?

So that’s essentially their defense. I mean, ah, okay, so they get – they arrive at the dock in New York and where – and where several newspapers had taken over a hotel and created a huge newsroom, and they went and grabbed these two telegraphers who had somehow been communicated that they could sell their stories for four figures.

And, and they wrote the story and, yes, they had – they had – they had the rights to the story after paying –

[0:45:00]

for it and so does that limit the news spread? Well, it was in the New York Times and it was – and the story was repeated in papers across the country. So, I guess the public got the story, but they insist they never contacted the Carpathia until it docked.

And, ah, and, and one of the other defenses they made in their editorials and stories was that the criticism of the rumors and the false allegations were maybe made by newspapers envious of the work they were doing, and they insisted the allegations in the inquiry were based on those rumors and false allegations.

Teri Finneman: So what do you think journalists today should take away from the aftermath of news coverage of the Titanic?

Ron Rodgers: Well, first of all, there’s the seeds of the notion of press responsibility to society, okay? Ah, let’s –

[0:46:00]

keep in mind, and I’ve written about this in other places before, is in the fact that this is early 20th century. Partisan press reigned in the 19th century, but incrementally was falling away, and by the early 20th century it was pretty much marginalized, though it still existed, but now it was the commercialized press, and the New York Times is a very good example of that.

Ah, so in the partisan press, reporters, journalists, they knew who they served. They served the political party that paid for their paper, but in the commercialized press whom did they serve, right? And that’s a question that gets batted around in the early 20s, first couple centuries – or decades of the early 20th century. And, and finally you see it culminated in the Canons of Journalism in 1923 that they serve the public not private interests.

[0:47:00]

And, ah, and so the seeds of that notion I think began there, and those – that notion still has resonance today especially in this – you know, this world we live in now with media. Notice I used the word media and not journalism. So much of this media that people define as journalism, but from my point of view it’s not. Um, but in this – all these digital formats where, where is the public interest, right? So I think it still has resonance today to think about these things.

And in fact, one, one of the lessons, too, is about the role of that commercialized press, which is what we mostly live with today, versus the market, and market opposed to the mission of journalism. What is the mission of journalism? To serve the public interest, but we’re constantly battling –

[0:48:00]

with the market forces of, of any publication, newspaper, online site or whatever.

Also one of the lessons is in early rethinking of the practice of paying for news. One of the things I often say to my students is where do – where do all these ethical constraints come from? Let’s say we can do this, and we cannot do that, and you kind of see it early thinking – rethinking about that.

Teri Finneman: All right, well, we have had two fantastic guests on our show today. Ron, thank you so much for joining us.

Ron Rodgers: Yeah, my pleasure.

Teri Finneman: Thanks for tuning in, and be sure to follow us on Twitter @jhistoryjournal. If you like our podcast, leave us a rating and a review wherever you listen to podcasts. Until next time, I’m your host Teri Finneman signing off with the words of Edward R. Murrow. “Good night and good luck.”