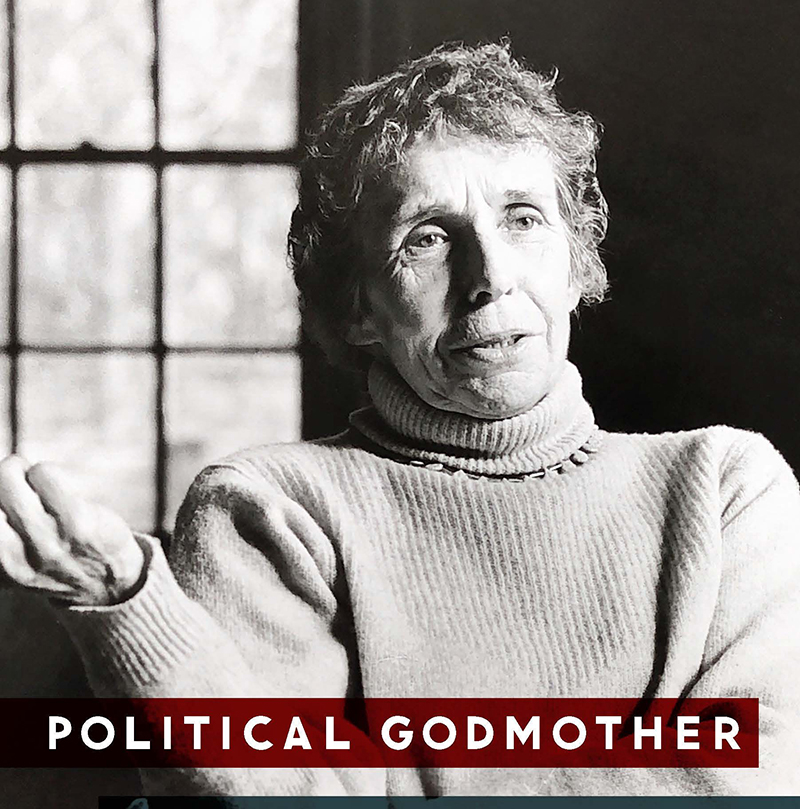

For the 55th episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Teri Finneman spoke to Meg Heckman about her new book “Political Godmother,” which discusses newspaper publisher Nackey Scripps Loeb, one of the most influential conservative voices in the latter half of the 20th century.

For the 55th episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Teri Finneman spoke to Meg Heckman about her new book “Political Godmother,” which discusses newspaper publisher Nackey Scripps Loeb, one of the most influential conservative voices in the latter half of the 20th century.

Meg Heckman is an assistant professor of journalism in Northeastern University’s College of Arts, Media, and Design. She writes regularly for a variety of publications about the intersection of gender, technology and journalism with a special focus on the experiences of female editors and publishers.

This episode is sponsored by Taylor & Francis, publisher of Journalism History.

Transcript

Meg Heckman:

What she wrote was, and still is very, very divisive. But she believed that she was doing the opposite of dividing people.

Teri Finneman (00:16):

Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to re-examine the stories you thought you knew and the ones you were never told.

Teri Finneman (00:26):

I’m Teri Finneman, and I research media coverage of women in politics.

Nick Hirshon (00:31):

And I’m Nick Hirshon, and I research the history of New York sports.

Ken Ward (00:36):

And I’m Ken Ward, and I research the journalism history of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Teri Finneman (00:41):

And together we are professional media historians guiding you through our own drafts of history. Show transcripts are available at journalism-history.org/podcast. This episode is sponsored by Taylor and Francis, the publisher of our academic journal, Journalism History.

Teri Finneman (01:00):

Newspaper publisher Nackey Scripps Loeb was one of the most influential conservative voices in the latter half of the 20th century. As the head of New Hampshire’s Union Leader from 1981 to 2000, she was a rare female leader in the news industry, and she was determined to make her newspaper a political powerhouse. Born into the prominent Scripps newspaper family, Loeb was best known for her editorials through which she would lay out “conservative arguments laced with God, family, folksy humor and her vision of a free society.”

Teri Finneman (01:36):

On today’s show, we visit with Meg Heckman, author of Political Godmother: Nackey Scripps Loeb and the Newspaper That Shook the Republican Party. Meg, welcome to the show. Before we get into Nackey’s newspaper career, let’s just touch briefly on her famous grandfather, EW Scripps, a legend who created a media conglomerate. Tell us about Edward Willis Scripps and the empire he started.

Meg Heckman (02:03):

Well, EW Scripps is this fascinating, larger-than-life figure in the history of American journalism. He created what many people now consider the first modern newspaper chain, and he pioneered a number of managerial and business strategies that would be very familiar to anybody who worked in newspapers in the last 30 or 40 years. So he had a number of newspapers. They weren’t terribly huge. They tended to be mid-size newspapers in communities all across the United States. And he operated them as a chain. There was lots of local content, but there was also a lot of shared content and he experimented with syndication, collaboration and a number of other things that really kind of laid the foundation for the newspaper industry during the second half of the 20th century.

Teri Finneman (03:21):

Nackey’s father Bob ended up as the chain’s editorial director when he was 27. He was in charge of 24 newspapers and a readership of 1.5 million. What was her childhood like in a newspaper dynasty?

Meg Heckman (03:36):

She was a very well-traveled little kid. She crossed the country most likely by train before she was six months old. And her family was big. It was a big family inside an even bigger extended Scripps family. And so she split her time between the family’s home on the East Coast in rural Connecticut, which gave her dad access to some of the bigger newspaper operations in the East Coast, along the East Coast. So she spent about half the year there and then the other half of the year she lived at a place called Miramar, which was a family compound that EW Scripps had constructed in Southern California outside of San Diego. And it doesn’t exist anymore. It’s now paved over from what I understand, but it sounds like it was just wild and rough and tumble and the children were really left, you know, their material needs were met, but they were really left to their own devices to kind of settle squabbles and keep on top of their schooling and, and that sort of thing.

And so she worked in the agricultural fields. She rode horses sometimes competitively. She went on cattle drives with her aunt’s side of the family and ate from a chuckwagon. And she and her sister slept under the stars in the desert. And her mother thought it was very unladylike, but she just grew up a little bit wild, a little bit free, and kind of became this really multifaceted multi-talented human. And I think she applied that unusual upbringing in a variety of ways throughout her career.

Teri Finneman (05:34):

Despite this history, Nackey wasn’t on a path to join the newspaper business herself until she married William Loeb. In 1946, William bought the Union Leader newspaper, which is the focus of what we’ll be talking about today and established a strong conservative voice in its pages. Give us some background more broadly on the formation of the conservative media in the mid-20th century and the idea of liberal media bias that formed.

Meg Heckman (06:03):

Sure. So William Loeb was part of a small but powerful network of right leaning media owners that began to coalesce in a variety of ways around the mid part of the 20th century. And their origins and their impacts were really well-documented. I’m going to plug another author’s book here, an academic by the name of Nicole Hemmer. She wrote a book called Messengers of the Right and it’s a fantastic deep dive into how a number of those early right-wing media owners got their start and the impact that they started to have. And as she says, the medium was very much key to the movement. So kind of one of the things that signaled that you were a member of this nascent political right was that you listened to a certain type of local radio or you read a certain type of local newspaper or subscribed to a right-leaning magazine. And part of that zeitgeist was this idea of liberal media bias that what we would call now the, the mainstream media was acting in a way that was counter to the beliefs and the goals of the right wing. And this whole movement evolved in ways fairly subtle over the course of many decades, and then really kind of percolated and exploded in the 1970s in what we refer to as the New Right.

Teri Finneman (08:07):

Related to this, I think it’s interesting to point out that Nackey, a strong conservative herself, even criticized her own Scripps family for their coverage of Senator Joseph McCarthy, known for his controversial anti-communism rhetoric. Tell us that story.

Meg Heckman (08:24):

Oh, yeah. This is, I think, one of my favorite anecdotes in the book. So shortly after Nackey married William Loeb and they were running the Union Leader together and it was very much a team operation. She preferred to work in the background. She was a self-described silent partner and she really didn’t insert herself into the political debate of the day a whole lot during their marriage with a couple of key exceptions. And one of them was when the Scripps newspaper chain ran a lengthy, multi-day series called the McCarthy Balance Sheet. And it was a deep dive into many problems with how McCarthy was handling, you know, handling the Red Scare basically. And that, you know, his anticommunist efforts had gone too far is what the journalist who wrote these stories argued, and it was at a time when opposition to the tactics used during the Red Scare was really coalescing and new policies were starting to be put into place.

And this is a wild oversimplification of a rather complex moment in US political history. But the important thing to know is that this series ran on the front page of virtually every Scripps Howard newspaper in the United States over the space of a week. So it was in living rooms on breakfast tables all over the country. And Nackey, she took issue with the existence of the coverage and the tone and the framing. And she decided to vent her frustrations by writing a letter to her brother who was at that point a top executive at the Scripps Howard chain. And I mean, it’s not at all uncommon for siblings to squabble over politics. It happens all the time. But what was different was these two siblings had very, very loud large platforms to kind of air their political differences.

And so she wrote this letter to her brother and then, to make sure that the letter got attention outside the family, they covered it in the Union Leader, which is a story about it on the front page of the Union Leader. And William and Nackey Loeb made sure that a copy of the letter got into the hands of some friends in the New York media. So this entire kerfuffle between Nackey Loeb and her brother at the Scripps Howard chain turned into this national story that persisted throughout quite a lot of that summer. And it really pointed towards a couple of things. One, the split between what we would call mainstream media and the nascent right-wing media and also Nackey’s willingness to insert herself into the national conversation when necessary. And it also marked her, it also marked her debut on the national political stage.

Teri Finneman (11:57):

William and Nackey were living in Nevada, but running this newspaper in New Hampshire. They eventually moved there, but how did they manage to become so powerful? By 1966, the Union Leader had a circulation of nearly 54,000 in a state with fewer than 200,000 households. And Nackey would later go on to even get the attention of President Ronald Reagan and other major conservative figures. So how did they become so powerful?

Meg Heckman (12:26):

Well, around the same time that William Loeb bought the Union Leader and married Nackey, New Hampshire was taking on a greater role in national politics because it’s home of the first-in-the nation presidential primary. So New Hampshire actually had the first primary since the early 1900s, since Progressive Era reforms led to the wide adoption of primaries and caucuses. But it didn’t really matter until the 1950s when the names of the actual candidates as opposed to their delegates appeared on the ballot. And so around that time, the New Hampshire primary began to take on this kind of almost theatrical, almost theatrical flavor and narratives about the New Hampshire primary really became embedded in political journalism. And the Loebs were able to leverage the increasing influence of New Hampshire and its presidential primary to really vote themselves into the national political landscape and become incredibly powerful figures. So candidates, political prospects could be seriously damaged by negative coverage in the Union Leader or negative editorials written by William Loeb and later, after his death, by Nackey Loeb. The Union Leader’s endorsements were not always the golden ticket to the White House or to another political office, but if the paper was not on a candidate’s side, the candidates that the paper opposed would just have a much harder path to victory. So the paper was really, really quite powerful and quite divisive both within the state and beyond the state.

Teri Finneman (14:34):

After William died in 1981, Nackey took over the paper. She faced a public perception that she wasn’t capable of running the paper due to her gender and her disability since she used a wheelchair after a car accident a few years earlier. How did she overcome this?

Meg Heckman (14:51):

Yeah, so when she took over as publisher, the narratives that emerged first, her rise to publisher was extremely well-documented in both the regional and national media because the future of the Union Leader was a huge question with the 1984 presidential primary kind of already starting to get underway. And so a lot of people wanted to know now that William Loeb was dead, would the Union Leader still have any political clout? And when Nancy first took over as publisher, the conventional wisdom, which was just spiked with rage-inducing amounts of sexism and ableism, even for that time period, the conventional wisdom said no, that she was kind of this meek woman who could not possibly actually be in charge of the paper. She would be a figurehead. Politicians no longer had to worry about what the Union Leader had to say about them.

And oh, by the way nobody really understood how she would be able to run a paper because she needed to use a wheelchair as a result of her paraplegia from the car accident. Well, Nackey very quickly and very strategically proved them wrong. So she immediately put herself on this kind of local community engagement tour. She spoke to women’s clubs, she spoke to chambers of commerce. She spoke at the local Boys and Girls club and really put herself out there. And every time she gave an appearance, her own paper would cover it and it would also often get picked up by other papers. And she also just really made a point of, you know, a lot of people would ask her questions about her disability and she spoke very openly and very honestly about that. And one of the things that she said was that having to go through the recovery process and the rehab process that she had to go through after the accident, gave her the confidence to take over the paper.

She often said that she wondered if she would have had the confidence in herself to take over the paper and operate in a world that was at the time very male-dominated and very competitive had she not had to go through that experience of basically learning how, relearning how to live her daily life and manage the challenges of her injuries.

Teri Finneman (17:44):

You mentioned in your book that much attention is given to progressive women and their activism in the feminist movement, but tell us more about the impact of conservative women in the latter half of the 20th century.

Meg Heckman (17:57):

Yeah, so it’s a really interesting period in political history. And I think it is — the best-known version of the narrative is how Phyllis Schlafly fought the Equal Rights Amendment. And that’s so embedded in pop culture. It’s, you know, it’s, it’s part of that new Hulu series Mrs. America, which I haven’t seen yet, but I’m told it goes pretty deeply into the fight for and against the era. So a number of historians, all of whom are cited in the book and I would encourage listeners to definitely go take a look at their work too, have dug pretty deeply into the rise of what one historian calls housewife populism. And that’s this idea that after World War II, a lot of women became very, very active on the very far political right, mostly motivated by the threat of communism. So they were afraid of communism. They were afraid of the threat of nuclear war. They were worried about economic insecurity. And they were worried about integration, particularly in the South. And so these, these women started out, you know, going to school board meetings and testifying about policies or educational materials that they felt were too progressive or were as they would call it un-American.

And these women kind of helped lay the groundwork and define the contours of what would eventually become the political right, the right-wing movement. Women were very, very involved in Barry Goldwater’s rise to national prominence in the early 1960s. This concept of a Goldwater girl has been pretty well documented. And then during the early 1970s, while the Republican Party was kind of figuring out its future and its identity, women played a pretty big role in that, too, where you had these clashes between groups that were called Republican feminists and then kind of the more far-right, socially conservative women like Nackey, like Phyllis Schlafly, who were kind of the women of the New Right. And, you know, I think if we look at the Republican Party today, those tensions still exist. And it’s just a reminder of the role that women across the ideological spectrum have played in defining political movements and picking issues that matter and kind of shaping the political landscape in which we all operate today.

Teri Finneman (21:00):

Nackey became known for her editorials and wrote more than 1,600 during her tenure before she quit writing in 1999. Give us an overview of what she wrote about and some of her more famous pieces.

Meg Heckman (21:12):

Her editorials were fascinating to read. So I got a grant from Northeastern University where I worked to aggregate and digitize all of her editorials and we found thousands and thousands of them. And I think when we finally got all of them together, it was more than half a million words, which is a tremendous amount of content. And she wrote about everything from Iran Contra to the importance of dogs in local communities. And she would write one day about what she viewed as the evils of interstate banking and then the next day would be congratulating some local teenagers for starting a petition about an anti-skateboarding ordinance that she felt was an example of overregulation. And she was glad that they didn’t want more laws in their community. She was very consistent in her ideology. She believed in small government.

She was very socially conservative and would sometimes use her editorials to, you know, push back against what she viewed as social norms that were too progressive and, or excuse me, evolving social norms that she viewed as too progressive. And at the same time, she would also be writing about the importance of protecting the natural environment, the importance of voting. She cared very much about civic engagement and would often encourage people, even people who disagreed with her very strongly to write into the paper. And she would stress that she would publish pretty much any letter that the paper received, even if it disagreed with her very strongly. So what she wrote was, and still is very, very divisive. But she believed that she was doing the opposite of dividing people. She believed that by putting out things that she felt strongly about, putting those things out into the world, she would be encouraging people to engage with her and engage with their neighbors.

Teri Finneman (23:37):

Why did you want to write about Nackey, and what do you think is her legacy?

Meg Heckman (23:41):

Well, so I grew up in New Hampshire and when I first got started in, when I first got started in journalism, I ended up coming back to the state to work at a newspaper here. And you know, I was vaguely aware of the Union Leader’s history and, and I was vaguely aware of Nackey. And about 10 years ago, I got invited to teach a writing workshop at a community nonprofit that she founded right before she died. It’s called the Nackey Scripps Loeb School of Communications. And it does free and, and mostly free classes about writing, video editing, storytelling, First Amendment issues. And I got invited to teach this class, and I walked into the little school area. It’s in a former truck driving school in a strip mall. It’s kind of weird and frugal in all sorts of interesting ways.

And I walked in there and there was just all of this material on the walls about her and her history and her relationship with EW Scripps. And the person running the school at the time mentioned, oh, by the way, we have all of her personal papers in, you know, in this closet over here in banker’s boxes. And so in the back of my mind, I just started doing what a lot of journalists do. I just started thinking about, well, who was this person? What kind of impacts has she had? And I wondered if somebody had written her biography and I looked around and couldn’t find one, found very little about her in the historical record and was kind of surprised by that. And so that just kind of planted the seed. And maybe three and a half years ago, four years ago, I was able to negotiate access to a number of her papers and a private archive, and then was able to, like I said, get that grant to aggregate and digitize all of her editorials.

(25:50):

And then as far as her legacy, that’s something that I, you know, even after writing the book, I’m just not sure. I think her legacy exists on, on different levels. So locally, she made a number of business decisions at the end of her life that have kept the Union Leader locally owned. You know, it’s really hard to run a local newspaper these days and the Union Leader is not immune to any of those challenges, but the people who run it and the people who will make decisions about its future have roots in the local community. And, and I think, you know, I think she would have been pleased with that. And so I think that’s one legacy. When we look more at her ideological legacy and her impact on the modern political climate, it gets a little trickier. I think we can look at her life as an example of how, like I said before, women across the ideological spectrum have, have shaped modern political life and how their stories are often not fully told and are often omitted from history. And it doesn’t mean that we have to agree with them to tell their stories. But you know, their stories in many cases should still be told. And even those with complicated and divisive legacies, you know, it’s her story. It’s her legacy and it deserves to be out there and debated and discussed and, and understood.

Teri Finneman (27:40):

And our final question of the show is, why does journalism history matter?

Meg Heckman (27:46):

I don’t think we can really move forward in a way that is inclusive and accurate and representative of all segments of society without fully understanding the profession’s roots. You know, we have to look back to really understand where journalists have done things really well and where journalists have fallen short, and look at, look at those lessons from history and maybe try and find ways to apply them to making good decisions about the future of journalism for many years to come.

Teri Finneman (28:32):

Thanks for tuning in and additional thanks to our sponsor, Taylor and Francis, the publisher of our academic journal Journalism History. Until next time, I’m your host, Teri Finneman, signing off with the words of Edward R Murrow. Good night and good luck.