For the 21st episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Teri Finneman spoke with Denise Hill about the hidden figures in public relations history, the African-American practitioners long overshadowed by their white counterparts in history books.

For the 21st episode of the Journalism History podcast, host Teri Finneman spoke with Denise Hill about the hidden figures in public relations history, the African-American practitioners long overshadowed by their white counterparts in history books.

A veteran of corporate communications and public relations, Hill is an assistant professor in the School of Communications at Elon University.

This episode is sponsored by Elon University’s School of Communications.

Transcript

Teri Finneman: [00:00:10] Welcome to Journalism History, a podcast that rips out the pages of your history books to reexamine the stories you thought you knew and the ones you were never told. I’m your host, Teri Finneman, guiding you through our own drafts of history.

[00:00:24] This episode is sponsored by Elon University’s School of Communications, which delivers a student-centered academic experience and access to high impact experiential learning opportunities, educating students to become data driven storytellers. A private university in North Carolina, Elon leads the nation in the U.S. News ranking of eight programs that promote student success.

[00:00:49] Hidden figures. We like to think of history as an objective set of the facts as they happened. Yet who is writing history makes a significant difference as to what gets attention and what gets left out. In this episode, we visit with Denise Hill from Elon University about the hidden figures in public relations history, the African-American practitioners long overshadowed by their white counterparts in history books. Denise, welcome to the show.

Denise Hill: [00:01:19] Thank you, Teri.

Teri Finneman: [00:01:20] Tell us why you became interested in drawing attention to African-American public relations practitioners.

Denise Hill: [00:01:28] Well, the history of public relations in the United States currently includes a number of pioneers and this history is often presented in public relations textbooks. It is also presented in public relations professional associations, and the pioneers in this history are white men and those white men were indeed public relations pioneers. However, during my research I discovered that African-Americans and women were also practicing public relations around the same time as these white males. I also examined the work of these minority and female pioneers and saw no difference in the strategies and tactics that the white males implemented and the African-Americans and women implemented when they were practicing public relations.

[00:02:19] So, I concluded that the African-Americans and women were omitted from the history of public relations in the United States, which means that the current historiography is incorrect. So, I became interested in this because I wanted to correct that and to make sure that the history of public relations in the United States is inclusive because it is, given the facts, and I wanted to draw attention to these pioneers who have been excluded from history. In addition, the public relations industry overall is trying to increase the number of minority practitioners, and it’s beneficial that they see that they are part of the industry’s history.

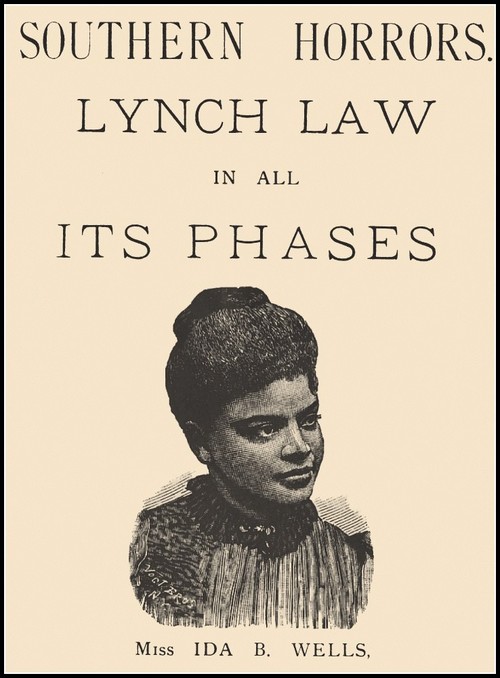

Teri Finneman: [00:03:03] So, let’s examine some of these individuals and their stories. Let’s start with Ida B. Wells. She’s generally known as a journalist, suffragist, and activist, but isn’t commonly labeled in history books as a public relations practitioner. So, let’s talk about her work with the anti-lynching campaign in the 1890s and the importance of that in PR history.

Denise Hill: [00:03:24] So, yes, she was a journalist, suffragist, and activist. She was not considered a public relations pioneer. However, she used public relations as part of her work as an activist and she used what we would call today public relations strategies and tactics to draw attention to the problem of lynching in the United States. She implemented a number of tactics to include, well, obviously she started as a journalist, so she used the news media to create awareness of the problem. She started first and foremost with research, which is what any public relations campaign needs to start with. And she found through her research that African-American men were being lynched because they were being accused of raping Caucasian women.

[00:04:16] And she found that most of the time those relationships were actually consensual, so she started out by presenting the actual facts because she wanted to dispute some of the reasons that people thought that African-American men were being lynched, so she used those facts and created messaging around those facts in her campaign. So, in addition to using the news media to create awareness of this problem, she also wrote a number of different pamphlets and used some face-to-face communication techniques. She went on a speaking tour in the United States and then overseas as well.

Teri Finneman: [00:04:54] Yeah. So, let’s talk about that overseas campaign. Why was it important to discuss this issue outside of the United States?

Denise Hill: [00:05:01] It was a way to draw attention to the issue not only by making people in other countries aware of the atrocity of lynching that was happening in the United States but there was additional attention paid to the issue because there was this awareness that other countries were aware.

[00:05:20] The same strategy was also used by labor, civil rights activists, especially during the Cold War. At the time, the United States was espousing worldwide democracy and freedom but it did not give its own citizens the freedom it demanded that other countries give their citizens. So, there was this hypocrisy associated with the fact that the United States was not doing what it asked other countries to do. And at the time, in the late 1800s, Ida B. Wells also capitalized on this. So, as the United States was trying to become more and more of a power and presenting itself as such, she wanted to draw attention to how this powerful country was treating its own citizens.

Teri Finneman: [00:06:05] In 1896, Wells formed the National Association of Colored Women. Why did she do that? And what were the immediate priorities that this organization promoted?

Denise Hill: [00:06:15] So, yes, she was one of the founders of the National Association of Colored Women. And in the late 1800s, I believe 1895, the president of the Missouri Press Association wrote a letter and this letter was in response to a letter that he received from a woman in England who was head of the English anti-lynching league.

[00:06:39] And this woman had asked the president of the Missouri Press Association to help. She was asking American journalists for help in battling lynching. And so this president of the Missouri Press Association wrote a letter in response and publicized that letter. And among other things in the letter, he attacked the morality and the character of black women. There were a number of black women’s clubs around the country so in response to this letter some leaders of these black women’s clubs mobilized and came together and said, ‘Strength in numbers. Let’s combine our clubs.’ So, they established the National Association of Colored Women in 1896.

Teri Finneman: [00:07:31] It’s interesting you mentioned strength in numbers because I don’t know if people today can fully understand the danger that Wells was putting herself in by speaking out on these kinds of issues. Is that something that you look into?

Denise Hill: [00:07:45] Yes, she did. So, she started out in Memphis. She had a newspaper there and that was destroyed because she was speaking out. So, she did face opposition and danger, physical danger by speaking out. So, the strength in numbers certainly helped in that regard. And that also helped because it allowed the message to reach a broader audience. So, the organization promoted political, social, economic reform, civil rights, education, and it also was an active supporter of the anti-lynching movement.

Teri Finneman: [00:08:22] Another notable figure in public relations history whom you discuss is Henry Lee Moon, director of public relations for the NAACP during major moments of the last century: Brown vs. Board of Education, the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act. Talk about who he was and then his strategies for managing the messaging in these major events.

Denise Hill: [00:08:44] Henry Lee Moon was the director of public relations for the NAACP from 1948 to 1974, so that’s twenty-six years. And during that period he worked on many of the pivotal events that you mentioned in the modern Civil Rights era. He was a public relations person, so unlike Ida B. Wells, who practiced public relations as part of her work as an activist, Henry Lee Moon was actually a public relations practitioner. He started out as a journalist before joining the NAACP. He was a press agent for the Tuskegee Institute. So, he implemented a number of strategies and tactics. He recognized that the purpose of the NAACP’s public relations program was to enhance the public image of the organization to gain acceptance in support of the association’s goals. And he recognized that the organization was engaged in the promotion, what he referred to as the promotion of ideas, and not in the production of commodities.

[00:10:03] And he recognized also that the NAACP’s work was very, very difficult because it was focused on challenging deeply rooted prejudices. So, he focused his efforts on those programs and one of the strategies that he implemented was he focused on audience segmentation, and he identified that the public relations program’s efforts needed to be focused on various audiences and those audiences needed to be segmented. He recognized and, in his words, he said, ‘There is no entity called the public in general.’ He said, there are actually many different publics and each of those publics have different relationships and different outlooks. So, he first segmented the publics into a black public and a white public and then he divided the white public into three different segments. The first segment he referred to as basically, he referred to them as a hostile group that was opposed to everything the NAACP stood for. And the second white public he referred to those as people who find that, in his words, ‘the teaching of democracy and their religion in conflict with the practices.’

[00:11:31] So, these are people who may be a little more open to civil rights and to recognize that all human beings should be treated equally. And then this third group was white people who are basically already committed to the work of the NAACP. And then the other segment was the black public. And he decided, he said, we should not focus our efforts on taking this segment, the hostile white minority group, as part of that white public. He said, ‘We are not going to convert that group. What we should do instead is focus on the black public and members of the white public that we can actually convince of our position and those who are already with us.’ And he said, ‘We can use that group and have that group be our supporters.’ So, that was a very important strategy and that strategy was also used later by other civil rights groups.

Teri Finneman: [00:12:31] That’s really interesting. So, now that they have these groups divided into these segments, what were some of the specific strategies they used to make their messaging effective for those groups they felt they could reach?

Denise Hill: [00:12:41] Some of the strategies that Henry Lee Moon used, so, the news media obviously was a strategy so he had a publicity program that was targeted not just in African-American newspapers but in white newspapers or mainstream papers as well. Now some of those papers would not run some of the material that he would send, but that was a strategy that he employed.

[00:13:10] The other strategy that was employed was one of identifying. So, this white public where there were supporters, to use those supporters to then sort of give testimonials and to further the message among their own constituents. So, the white audience that was already active in supporting the NAACP, what Moon did – so, some of those people would be speakers on behalf of the NAACP. They would be the ones that would speak to other white audiences. So, that was one of the tactics that he used in terms of using speaking engagements that was very popular, that was also used by other civil rights groups.

Teri Finneman: [00:13:53] What strategy differences or similarities are there with the messaging during the Civil Rights movement in the ‘60s and with the more recent Black Lives Matter movement?

Denise Hill: [00:14:03] So, it’s interesting, because regarding messaging and crux of the overall messaging it’s very, very similar and that is that there is a group of people who has been denied the same rights or has been treated differently or had acts perpetrated on it that are not the same as members of the majority group. So, the underlying similarity of messaging is one of equality and pointing out the lack of that equality and demanding equal treatment. So, that message was prevalent during the civil rights movement and is also prevalent, in unfortunately that it still needs to happen, in the more recent Black Lives Matter movement.

Teri Finneman: [00:14:56] So, talking about another public figure, I’m really interested in the work of Moss Kendrix. He started his own firm in Washington D.C. and advised Coca-Cola and other brands and played a big role in convincing companies to stop running stereotypical advertising with figures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. So, how was he able to convince these companies to change their strategies?

Denise Hill: [00:15:20] So, Kendrix was actually not the first to do this. There’s something called the cola wars, and Pepsi Cola, in the late 1940s, had hired an African-American sales executive and he amassed a small sales force that targeted the African-American community. And he also launched some ads targeted at the African-American community in the late 1940s. And Pepsi and cola, the cola wars, had started in the 1930s. So, Moss Kendrix recognized that Coca-Cola Corporation had not targeted the African-American market. Pepsi had targeted the African-American market. So, he developed a proposal and presented it to Coca-Cola Corporation. They did not accept it right away. It took him a number of years. He first presented this around the same time that Pepsi was doing its work, which was in the late 1940s, and then as Pepsi started gaining market share and market share from Coca Cola, Coca Cola recognized that, here was a segment, a consumer segment, that it had ignored.

[00:16:26] And there were a number of companies that had ignored the African-American consumer segment because these companies did not think that African-Americans were really consumers. And then after World War II, the increase in the economy, the improvement in the economy, the African-American consumer segment started to grow and companies started to recognize the power of it. So, Coca-Cola was one of those companies and Moss Kendrix was able to convince Coca-Cola that it could gain significant market share, hence improve the bottom line. And he was able to convince Coca-Cola Corporation to hire him as the agency of record targeting marketing communications to the African-American market.

Teri Finneman: [00:17:20] Kendrix began by convincing Coke to include black celebrities in ads but then shifted to including everyday black men and women in ads in the mid-1950s. Talk about the significance of this to not only the black population of the time but also the white population.

Denise Hill: [00:17:36] So, one, this idea of African-Americans as consumers. That’s something that Moss Kendrix wanted to show, so getting away from the stereotypical images of African-Americans that had been in ads. Those images were not of African-Americans as consumers and Pepsi had started this in the 1940s, showing an African-American middle class, African-Americans as consumers. So, Moss Kendrix did the same thing in his advertisements. So, Coca-Cola and Pepsi Cola both were targeting African-American consumers and as a population who was consuming its products, it wanted to show the consumer as it was targeting them.

[00:18:26] So, it was a change because, again, as you mentioned, advertising had shown African-Americans in these very stereotypical ways such as Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. And Pepsi and Moss Kendrix made significant changes in that area by depicting African-Americans as consumers and a very, very active middle class, showed families consuming Coke, enjoying Coke very similar to the way or similar to the way that Coca-Cola and Pepsi Cola had been advertising to the white population.

Teri Finneman: [00:19:06] How do you think companies are doing today as far as understanding the importance of targeting diverse markets?

Denise Hill: [00:19:13] Well, certainly better than they did in the 1930s and ‘40s, so significant improvements in that area. But even today, some companies have made some significant marketing errors. I won’t point out specifics. There have been a number recently, some fashion-related brands have made some errors, but it’s not just fashion companies have made some significant, what we would call marketing fails or marketing communications fails. So, there are improvement opportunities in that area.

[00:19:48] However, companies and their advertising and public relations agencies need to do a much better job of hiring minorities in all levels of the company. So, part of the issue with some of these marketing fails is some of the people who are implementing marketing programs are not the target audience, so you don’t have African-Americans working in executive management ranks or in senior management ranks. So, I think there were some significant improvement opportunities on the corporate side, on the advertising and PR agency side to hire more minorities and especially minorities at more senior level ranks.

Teri Finneman: [00:20:34] Inez Kaiser is another figure in PR history who hasn’t received much attention. She started the first African-American female-owned public relations firm in the country and her clients included 7-Up and Sears. Tell us about the significance of her work.

Denise Hill: [00:20:54] So, Inez Kaiser’s significant. She is one of the pioneers. So, earlier I mentioned that in the public relations profession, in the industry, there are a number of pioneers. Most of those pioneers currently are white males. So, Inez Kaiser should be included among the pioneers because she was a first and that’s why her work is significant. She started a public relations agency in 1957, and she was the first African-American female to do so, as you mentioned. So, that is significant and it was 1957. We’ve still got some issues with Jim Crow in 1957, still discrimination, significant discrimination, in 1957. So, the fact that she was a first was significant in and of itself.

[00:21:46] She was also the first black-owned business in Kansas City, Missouri. So, not just the first black-owned PR agency but the first black-owned business in Kansas City, Missouri. So, the fact that she was a female, the fact that she was African-American, the fact that it was a public relations agency, and also the significance of some of her accounts, she had not just local accounts, but she had some important national accounts such as 7-Up and Sears. So, she also needs to be recognized. She’s one of these overlooked practitioners who should no longer be overlooked.

Teri Finneman: [00:22:25] Speaking of overlooked, the New York Times recently ran a story called Overlooked, which featured remarkable black men and women who didn’t receive obituaries in the paper. How can we go about rectifying the overlooked parts of our nation’s history?

Denise Hill: [00:22:41] I think one of the first things we need to do to do that is to pose the question, why didn’t those black men and women receive obituaries and recognize what the answer to that question is, which has to do with our country’s history of racial problems, which continue today. And those problems impact how our history has been presented, and not just in terms of presenting obituaries in the New York Times, but also in the area that I study, in the area that I practice, public relations, and then the question becomes, how many other areas are there where contributions of black men and women have been overlooked?

[00:23:28] A couple of years ago, we had the film Hidden Figures about African-American female scientists, so yet another area. So, when we look at our history, we need to be aware that there were groups that were excluded. And that often those groups are sometimes women, sometimes African-Americans, men and women, and that means that our history is incomplete and therefore, inaccurate. So, when we realize that, we need to conduct research to identify who was excluded and then give them the visibility that they did not initially receive.

Teri Finneman: [00:24:22] Our final question of the show, as always, why does journalism history matter?

Denise Hill: [00:24:28] Well, one of the reasons it matters is because journalism is such an important part of society. It contributes to the functioning of a democracy and civil society. And it chronicles our society and therefore, is a chronicler, it chronicles history. And aspects of our history are learned through the news media. And from a public relations standpoint, one of the strategies that public relations practitioners employ is using the news media to generate awareness. If you look at awareness of the modern civil rights movement, a lot of that awareness, what was happening in parts of the country, U.S. citizens became aware of that through the news media.

So, what was happening for example in the South. There were citizens in other parts of the country that were not aware of that and they became aware of that through the news media. So, that’s one of the many reasons that journalism and journalism history is so important. We learn about society through journalism, and learn where we have been successful, and we learn where we still have to improve, and that’s where we are in the United States today. And that’s one of the reasons that history overall is so important and that journalism history is so important and that public relations history is so important. We can look at what was done in the past to learn about it, and we can also look at what was done in the past as we try to improve our society and figure out where we have not made strides. And we can use some of those techniques that were done in the past and continue some of those today. So, journalism history is very important, public relations history is very important as well.

Teri Finneman: [00:26:20] Great. Well, thank you so much for joining us today.

Denise Hill: [00:26:22] Thank you, Teri.

Teri Finneman: [00:26:25] Thanks for tuning in and additional thanks to our sponsor, Elon University, and to Taylor and Francis, the publisher of our academic journal, Journalism History. Until next time, I’m your host, Teri Finneman, signing off with the words of Edward R. Murrow: Good Night and Good Luck.

1 Comment