Writing about white supremacy during the summer of the George Floyd protests

We must confess that our article in this issue of Journalism History was not born out of some high-minded desire to grapple with profound and difficult questions about American racism. Rather, it grew out of an enthusiasm that is both juvenile and shallow by definition—a shared love of adventure stories for boys and travel journalism. We knew that since the earliest days of the republic, American correspondents have returned from abroad to publish chronicles of war and of exploits in far-off lands, and we wanted to understand this rich vein of journalism history. We also knew that while volumes have been written about Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Jack London and Ernest Hemingway, scores of journalists who produced similar narratives for dime novels and pulp fiction magazines have been almost entirely ignored.

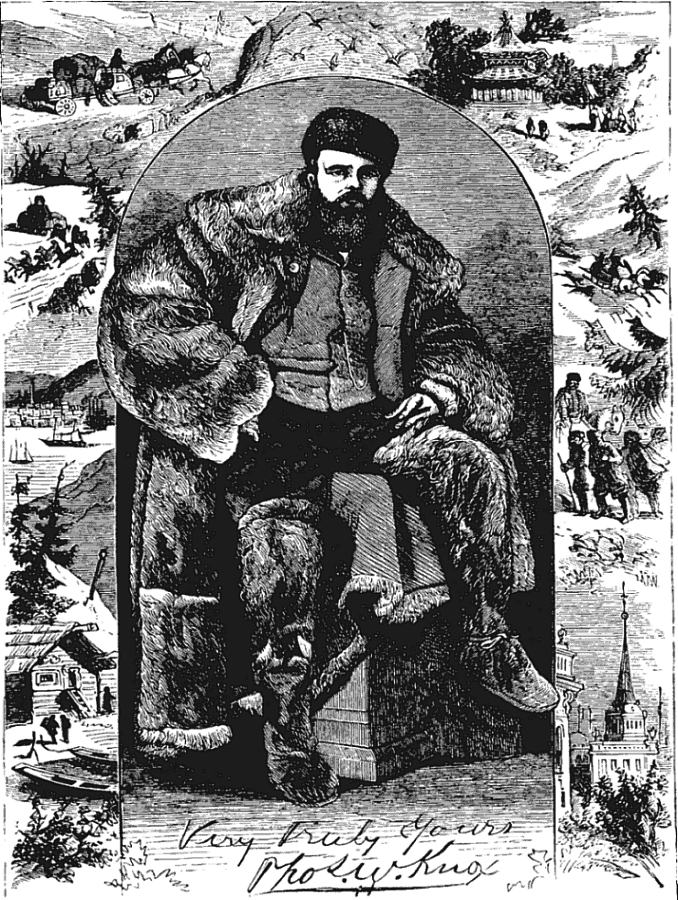

Perhaps, if we had realized from the start that we were racing into a minefield, we would never have tried to tell the curious tale of Civil War reporter Thomas W. Knox. But as it turned out, we discovered with some amazement that during the summer of 2020, in recounting this history, it was as if we had been transported back to being reporters ourselves again, covering breaking news about the most highly charged, divisive controversies of our own day.

Protests raise questions

By the beginning of last July, the nation was in the throes of what was likely the largest protest movement in its history, ignited by the police killing of George Floyd just five months before Election Day. Donald Trump’s incumbency had already guaranteed that race would be the salient issue of the “silly season,” but the searing nine-minute video of Floyd’s murder poured rocket fuel on the fire. Heading into Independence Day, the New York Times reported that between sixteen and twenty-six million people had participated in over two thousand demonstrations in some sixty nations.[1] Black Lives Matter activists were clashing with Trump’s “law and order” army over which narrative of America and its past would prevail.

Just as “people make the news” in journalism, stories of individuals give form and meaning to history. That is why the two of us mostly write biography, and also why monuments honoring Confederate generals have been flashpoints in our society’s contests over the American story. The drive to remove Confederate monuments was first sparked back in June 2015, by a white supremacist massacre in a church in Charleston, South Carolina, just one day after Trump had announced his presidential candidacy with a description of Mexican immigrants as drug dealers and rapists.[2] But during last summer’s George Floyd protests, the battles over monuments expanded radically, in ways that are deeply revealing of how our politics and culture make use of history.

The feud over Confederate monuments had continued, with protesters in Richmond, Virginia, besieging the statues of Gen. Robert E. Lee, Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, President Jefferson Davis, and Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart.[3] But now Trump was leading a right-wing charge into new territory, holding a July Fourth rally at Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota, on land sacred to the Lakota Sioux that was taken from them in the nineteenth century. Trump began with a flourish, announcing that federal agents had nabbed the “ringleader” of an attempt to tear down a statue of President Andrew Jackson, the “Indian Killer” who had earned that soubriquet for his implementation of the genocidal Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears. Our commander in chief then added that he had just signed an executive order to ensure that anyone found guilty of damaging a national monument would face a minimum of ten years in prison.[4] His supporters, who the day before had taunted and clashed with Native American protesters, now celebrated America’s birthday with a military flyover and fireworks that were allowed after overturning a ban that had been implemented to protect the Lakota land.[5]

Activists on the left, meanwhile, were also forging ahead, triggering what the Wall Street Journal called a new “reckoning over (the) nation’s history.”[6] Perhaps the toppling of statues honoring former slaveholders George Washington and Thomas Jefferson was unsurprising. Now the protests extended to monuments of colonizers in New Mexico and California, where local and state governments removed statues of the Spanish Catholic missionary Father Junípero Serra and the despotical Spanish colonial governor Juan de Oñate amid outcry over mistreatment of Native Americans in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries.[7]

But now also, protesters tore down a statue honoring Ulysses S. Grant in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, and they called for the removal of Abraham Lincoln monuments in Washington, D.C., and at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “For him to be at the top of Bascom as a powerful placement on our campus, it’s a single-handed symbol of white supremacy,” declared Black Student Union President Nalah McWhorter.[8]

The questions hanging in the air were these: Was America a fundamentally racist country, built on a foundation of racism? Was its very bedrock, including the Constitution itself, “structural” racism? And was the country, therefore, irredeemably racist?

Knox research offers context

With this din of demonstrations and polemics roaring in the background, we applied ourselves to disentangling the complicated story of Thomas W. Knox. And in the process we learned a few things that we believe help answer those questions.

At first blush, this staunchly pro-Union Civil War correspondent would appear to have held strikingly enlightened views for his day about race. After being stripped of his press credentials for an alleged violation of federal orders, he had conducted a bold experiment on a newly liberated cotton plantation. Knox had defied local Confederates by trying to prove that free labor could be just as profitable as slavery, and he nearly sacrificed his life in the effort. Yet here was the curious twist to Knox’s story: Over the next twenty years, he traversed the globe writing travel books for boys that were explicitly racist and paternalistic in ways that would color American expansion, at home and abroad, for decades to come.

There were, in fact, a number of difficult questions wrapped up in this tale: How did Knox understand race, and how in turn are we to understand him, within the context of his time as well as our own context today? And how can anyone have a sense of what a country as a whole believed about race?

In regard to the second question, scholars like Reginald Horsman, Eric Foner and Manisha Sinha have done deep dives into the discourses of the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. But beyond that, the actual legal codes and published science of those decades are perhaps most telling. For example, the popularity of phrenology during the 1840s, and the shift during the era from monogenesis, the belief that all races descended from Adam and Eve, to polygenesis, the theory that all races had genetically determined prospects for development, demonstrate that science was hardly objective, but it was in fact under the sway of the dominant political and cultural currents of the time. Still, different people believe different things, and attitudes at any given time can vary considerably. Cultural historian David Wrobel cautions against framing all travel writers as imperial agents, noting that readers of the time “would not have experienced any kind of harmony in travel writers’ descriptions or assessments.”[9]

Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, people are as contradictory and complicated as history itself. They may not say what they really mean, particularly on as sensitive a topic as race. They may not be clear in the first place about what they believe, or may hold views that are inconsistent, or may change their minds radically over the years. So while historians are often warned to avoid psychologizing and to stick to the facts, we found that psychology was key to arriving at any kind of truth about the facts at hand. We applied our insights not only to Knox, but also to what Knox’s story might tell us about American society as a whole.

In trying to understand both, we were particularly struck by pro-slavery writer George Fitzhugh’s remark that those who most sympathized with the fate of the American Indian “would be the first to shoot him if they lived on the frontier.”[10] We noted that Knox’s views of African Americans were quite benevolent while he was mounted on horseback as overseer of his cotton farm. But by the 1870s, he was wandering around Latin America and the Holy Land, alone and outnumbered. He was suddenly vulnerable, feeling the gaze of the brown people who surrounded him, and the fear and contempt poured out of him, onto the pages of his travelogues.

Our best secondary sources suggested that the whole of his society had been on a similar trajectory from the time of America’s founding to Knox’s own day. “While some Americans in the years after the Revolution talked and wrote easily of how they would share with other peoples the freedoms that had been so happily bestowed on them,” argued Horsman, “this dream was already being challenged not only by pride in a peculiarly English heritage, but also by the reality of black slavery and warfare with the Indians. Proponents of expansion in the early years of the American Revolution found it far simpler to think of improving other peoples in abstract rather than in practical terms.”[11]

Certainly, the racism was structural, but many of those structures actually developed and hardened over time. As Foner points out, “The American Revolution threw the future of slavery into doubt.” Nearly 100,000 slaves deserted their owners to fight for the British, while thousands more escaped by enlisting in the Revolutionary Army. By 1800, nearly all Northern states allowed for gradual emancipation, and all allowed suffrage for men regardless of race. Still the Constitution permitted the slave trade from Africa to continue for another twenty years, required states to return fugitives from bondage, and counted three-fifths of the slave population in allocating electoral votes among the states.[12]

So is the United States built on racism? The answer we found was yes … and no. To deny that altogether would be to whitewash history. But to affirm it would be to blot out aspirational principles that were there from the start and have been so important to Americans of diverse origins all along. That, too, has always been part of the American story.

Is America built on white supremacy? A simple “yes” or “no” answer would do violence not just to our past, but to our present as well as our future prospects. White supremacy is part of our nation’s complicated past, but so are notions of the perfectability of humanity. White supremacy need not determine our future, but to prevent that, we must first understand the role it has played, the ways it has played out, and the damage it has done. Only then can we reconcile the past with our turbulent present and pursue a more just future.

About the authors: Julien Gorbach, an assistant professor of journalism in the School of Communications at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and Michael Fuhlhage, an associate professor in the Department of Communication at Wayne State University, are the authors of “Fallen, Broken Places: American Imperial Journalism and Thomas W. Knox’s Traveller Books for Boys” in the June issue of Journalism History.

References

[1] Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History,” The New York Times, July 3, 2020, accessed July 5, 2021: https://nyti.ms/3hBQkcL

[2] Robert McClendon, “New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu calls for removal of Lee Circle statue,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), June 24, 2015; Kevin McGill, “Analysis: Did the Emanuel AME Church massacre push New Orleans to remove Confederate monuments?” The Post and Courier (Charleston, S.C.), May 14, 2017, accessed July 5, 2021: https://bit.ly/3wn5rfw

[3] Henry Graff, “Final Remnants of Confederate Monuments in Richmond Could Be Gone This Summer,” WHSV3, accessed June 11, 2021, at https://bit.ly/36bDMUm

[4] “Donald Trump at Mount Rushmore Speech Transcript at 4th of July Event,” Rev.com, accessed July 5, 2021: https://bit.ly/2ST6N4a

[5] Levi Rickert, “American Indian Protesters Told to ‘Go Home’ by Trump Supporters at Mount Rushmore,” Native News Online, July 4, 2020; Protesters Near Mount Rushmore Clash with Police, Trump Supporters, NBCNews.com, July 4, 2020; Jordyn Phelps and Elizabeth Thomas, “Trump at Mount Rushmore: Controversy, fireworks, and personal fascination,” abcNEWS.go.com, accessed July 5, 2021: https://bit.ly/3dIaTmM

[6] Andre Restuccia and Paul Kiernan, “Toppling of Statues Triggers Reckoning Over Nation’s History,” The Wall Street Journal, June 23, 2020, accessed: https://on.wsj.com/3qL3jx6

[7] Andrew J. Campa, “Junipero Serra Statue to Be Moved Away from Ventura City Hall,” Los Angeles Times, June 19, 2020, John Burnett, “Statues of Conquistador Juan De Oñate Come Down as New Mexico Wrestles with History,” National Public Radio, July 13, 2020, accessed June 11, 2021, at https://lat.ms/3Az6kVw, https://n.pr/3dOEMSC

[8] Lois Beckett, “San Francisco protesters topple states of Ulysses Grant and other slaveowners,” The Guardian, June 20, 2020; Kelly Meyerhofer, “University of Wisconsin students call for removal of Abraham Lincoln statue on Madison campus,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 2020, accessed July 5, 2021: https://bit.ly/3hiKM87, https://bit.ly/2TGsgh5

[9] David M. Wrobel, Global West, American Frontier: Travel, Empire and Exceptionalism from Manifest Destiny to the Great Depression (Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 2013), 81.

[10] George Fitzhugh, Sociology of the South (Richmond, Va.: A. Morris, 1854), 287.

[11] Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981), 97.

[12] Eric Foner, “Expert Report of Eric Foner,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 5, no. 1 (1999): 315-316, 317.